Coffee is one of the world’s most beloved beverages. It is obtained from the grinding of various species of tropical trees belonging to the Coffea genus. It is one of the most important commercial crops, and represents the second most valuable commodity after oil. The word ‘caffè’ (coffee) derives from the Arabic term ‘qahwa’, which anciently referred to a red drink, with exciting and stimulating effects, sometimes also used as a medicine.

There are several stories that are passed down about the origin of the beverage. The most famous legend features an Ethiopian shepherd named Kaldi, who, one day, saw his goats voraciously eating some red berries. He initially paid them no mind, but that night he couldn’t help but notice that all the animals couldn’t fall asleep. The shepherd thus decided to return to the place where he had seen these berries, took them with him, and after grinding them, made an infusion: coffee. And shortly thereafter, he felt a great energy pervade his body. Another version of the legend claims that Kaldi shared the berries with a monk, who initially disapproved of their use and threw them into the fire. Surprisingly, the result was a marvellous and pleasant aroma which, in fact, led to the first roasted coffee of all time. Soon after, the beans were ground and boiled to produce a beverage that must have been quite similar to what we know today as coffee.

Other legends attempt to shed light on the history of coffee. Its discovery is attributed to a disciple of the Shadhiliyya called Omar. According to the ancient chronicle, preserved in the manuscript of the Persian Abd al-Qadir Maraghi, Omar, known for his ability to heal the sick with the sole power of prayer, was exiled from Mokha (a city in Yemen on the coasts of the Red Sea) to a desert cave near Ousab, in present-day Eritrea. He, too, tried chewing the berries collected from some nearby shrubs, but found them bitter. He then began grinding them in an attempt to improve the flavour, but they became harder and inedible. He then tried boiling them to soften them, which produced a fragrant dark liquid. After drinking it, Omar was able to remain without food for entire days. When the tales of this ‘miraculous medicine’ reached Mokha, Omar was allowed to return and was later made saint.

In the 11th century, another eminent Islamic scientist, Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā, better known as Avicenna, mentioned coffee in his treatise ‘The Canon of Medicine’, indicating the beverage as a useful remedy to combat bad body odors and to promote mental clarity. Already between the 14th and 15th centuries, there is evidence revealing that coffee was particularly widespread in Arab countries. One of the most important early writers on coffee was Abd al-Qadir al-Jaziri, who in 1587 compiled a work that traces the history and the legal and religious controversies concerning coffee. He reported that the Sheikh of Aden was the first to adopt the use of coffee around 1454. He discovered that, among its properties, it could also counteract fatigue and drowsiness and simultaneously provide the body with a certain agility and vigour. The coffee plant was highly prized because it was considered magical, and for this very reason, the Arabs initially prohibited its export so as not to reveal the invigorating properties of coffee. Originally from Kaffa, Coffea arabica was introduced to Yemen and cultivated and exported from the port of Mokha / Mocha (from which the Moka, the coffee maker designed by the Italian Alfonso Bialetti in 1933, would take its name). The Arab country had long and intense trade relations with the Empire of Ethiopia. Around 50,000 hectares of coffee began to be cultivated in the two countries. In fact, the first credible evidence of the knowledge of the coffee tree appears in the middle of the 15th century, in the Sufi monasteries of Yemen. In Arabia, coffee was used to stay awake during night prayers but also for curative purposes. In the 15th century, the first coffee houses began to spread throughout all Muslim countries. In 1414 the beverage was known in Mecca, and at the beginning of the 1500s, it was disseminated in the Mamluk Sultanate and North Africa.

A myriad of ‘coffee houses’ were established in Cairo. Shortly thereafter, they also opened in Syria, especially in Aleppo. Meanwhile, the first coffee house on European soil opened in Istanbul in 1475. Even today in Turkey, coffee is prepared in the cezve (small pot), a narrow copper and brass jug with a long handle. By 1630, in Cairo alone, there were thousands of coffee houses stemming from the Sufism legend linked to coffee. But despite being a beloved beverage by the majority, the exciting effects of coffee did not meet the favour of Islamic law, and its consumption in public places was soon forbidden, and all coffee houses were closed. When the Sultan of Egypt continued to authorize its consumption and coffee reached its highest spread, an attempt was made to stop its success by declaring it to be the ‘devil’s drink’ and claiming that its consumption caused irreparable physical damage. But this did not serve to put an end to the history of coffee. Coffee had by then conquered everyone’s heart and palate, continuing to be drunk privately in the living rooms of homes.

The history of coffee in Italy began on a precise date and in a specific place: in 1570 in Venice, when Prospero Alpino from Padua brought some sacks of it from the Orient. In fact, the active mercantile exchange between the Republic of Venice and the Muslims of North Africa, Egypt, and the Ottoman Empire led to the introduction of a large variety of goods, including coffee, right on the routes of Venice, one of the main European ports of the time. The Venetian merchants introduced coffee to the Venetian aristocracy, albeit with some insistence. But in a short time, it also spread to the mainland, initially among students, lecturers, and visitors of the University of Padua. Soon, Venice became the coffee capital of the world. In 1683, the ‘All’Arabo’ café was inaugurated in Piazza San Marco. Shortly, the city could count a total of 200 cafés, about thirty of which overlooked the prestigious Square. In 1720, Caffè Florian opened, which is still the oldest existing café in the world. (https://caffeflorian.com/florian-venezia/storia/)

But Trieste also became an important center for the spread of coffee, not only in Italy but throughout Europe. In fact, in 1719 the city became a free port, thus transforming into the main mercantile hub of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and one of the major commercial centers at the European level. Numerous sacks of coffee began to arrive at the port of Trieste. They initially came from Turkey, Egypt, and Ethiopia, and gradually from other countries as well. Many businesses dedicated to processing the beans and powder, as well as selling the beverage, quickly developed, which would later solidify into the establishment of an entire coffee supply chain. The city’s first coffee house was opened as early as 1768. Furthermore, several prestigious roasting companies were born here, now known worldwide, including the historic Hausbrandt, created by the Zanetti family in 1832, and the famous Illycaffè, founded in the 1920s by the Hungarian Francesco Illy. The history of coffee in Trieste continued over time, with the incessant development of related activities. It even managed to record, at the beginning of the 20th century, the foundation of the world’s first Coffee Exchange. And what about Naples? Although it is known today as the city of espresso, it only later became acquainted with this historic tradition. Its diffusion arrived via foreign ships docking in the ports of Sicily and Naples itself. The first evidence of coffee use in Naples dates back to 1614, but some believe that coffee arrived in Naples even earlier, coming from Salerno and its Salernitan Medical School, where the plant was used for its medicinal properties between the 14th and 15th centuries. The Bourbons played a fundamental role. In fact, we owe a flood of culinary innovations in Naples to the couple Maria Carolina of Austria and Ferdinand IV of Bourbon. While the King greatly promoted the consumption of tomatoes and potatoes, and was also one of the major sponsors of pizza, the austere and elegant Queen imported numerous traditions, mostly confectionery, from Austria, but she was also very keen to bring Viennese coffee to the city. This was towards the end of the 18th century, and the beverage was already widespread and well-known throughout Europe, while the first coffee houses were starting to open in Naples.

Celebrated by art, literature, music, and Neapolitan high society, coffee quickly became a protagonist in the city of Naples. It was prepared with great care in the ‘cuccumella’, the typical Neapolitan filter coffeemaker derived from the invention of the Parisian Jean-Louis Morize in 1819. After the birth of the first Neapolitan coffee houses, all those rituals that characterize coffee in Naples today began to be codified: from the ceramic cup to the history of the caffè sospeso (suspended coffee). Meanwhile, coffee was spreading both in Europe and worldwide, and with it, the interests linked to its trade grew immensely, and contextually, the determination to remove the Arabs’ monopoly on the beverage increased. The Netherlands was successful, managing in 1690 to smuggle out – despite the strict vigilance of the Islamic authorities – some coffee seedlings, transferring them to the tropical lands of Ceylon (today Sri Lanka) and Java (in Indonesia). Through the Dutch East India Company, the Netherlands established itself as a benchmark for the European coffee market.

The seedlings that the Dutch merchant Pieter van der Broeck had smuggled from Mokha more than forty years earlier adapted to the local climate conditions in the greenhouses of the Amsterdam Botanical Garden. For the next half-century, the Dutch (and the Dutch East India Company) remained the masters of European trade, until a sensational misstep. When in 1714, the mayor of Amsterdam offered the King of France, Louis XIV, two flowering coffee plants as a special gift. They were placed in the royal greenhouses of Versailles and here, a former naval officer, Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu, stole one of the plants and transported it across the Atlantic. He thus began the cultivation of coffee in French Martinique, an island in the Antilles. In the subsequent fifty years, the plants from Martinique reached such a number that they could satisfy almost the entire European demand; soon the plantations extended throughout the entire Caribbean area, from Haiti to Jamaica, as far as Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Brazil became the last protagonist thanks to the Brazilian lieutenant Francisco de Melo Palheta. The story goes that a French general brought a coffee seedling with him to the overseas territories to produce its precious fruit. However, due to a fierce territorial dispute, the French had to clash with the Dutch: a Brazilian official (who at that time must have been of Portuguese nationality) was appointed arbitrator of the conflict. The Brazilian official, evidently on excellent terms with the wife of the Dutch general, managed to be given a seedling of this extraordinary fruit (we recall that the Dutch and the French monopolized the production of coffee in their territories). Thus, cultivation began to develop in the Brazilian lands as well: already after fifty years, it had expanded to unimaginable dimensions. Introduced to Brazil at the beginning of the 18th century, it quickly became a remarkable success: the tropical climate and the fertile lands around Rio de Janeiro favoured the expansion of the crops, so much so that Brazil became the largest coffee exporter in the world. The new crop further consolidated the dominance of the large landowners with the use of slave labour, and intensified trade relations with the whole of Europe. Furthermore, it caused a small earthquake in the political balance of the young country, effectively shifting economic power toward the southeastern regions. Rio de Janeiro, already the imperial seat, became the centre of intense commercial activity. Later, towards the end of the century, the exhaustion of the land around the city allowed the development of cultivation also in the area of nearby São Paulo. Coffee cultivation in Brazil is directly responsible for about one-third of global coffee production, thus making the country by far the largest global producer; a position it has continued to maintain for more than 150 years, followed by Vietnam, Colombia, and Ethiopia.

The origin of espresso

Espresso coffee is a type of coffee, the most consumed and well-known in Italy. Obtained from the roasting and grinding of Coffea arabica and Coffea robusta beans, it is prepared by machine according to a percolation process under high-pressure hot water. Espresso coffee finds its roots in instant coffee, which originated in Turin in 1884, following the invention of the machine to produce it, ‘La Brasiliana’, patented by Angelo Moriondo. This invention arose from the need to satisfy the demand of customers at his establishment in the center of Turin, in a shorter time than allowed by the methodologies used until then. From a technical point of view, the instant coffee machine consisted of a large, bell-shaped copper boiler. Through a steam mechanism, water was heated and channeled towards a bed of coffee grounds, which were placed in a metal filter. The term ‘caffè espresso’, in reference to instant coffee, was adopted for the first time by Desiderio Pavoni at the Milan Fair in 1906. The coffee produced with steam machines was very different from the current one, and would probably even be unpleasant for us today. It was a coffee with little body, not creamy, very bitter, and above all characterized by a burnt taste. The term subsequently became common usage to refer to instant coffee. The term ‘espresso’ was first included in the official name of a patent by Antonio Cremonese in 1936; this patent would later be acquired by Achille Gaggia, improved, and marketed as a machine for ‘crema caffè’ (coffee cream). This new name came from the fact that the coffee featured a layer of cream, which was absent in instant coffees. Crema caffè therefore became espresso coffee in the currently recognized form. Gaggia’s machine introduced a system based on pistons that pushed high-temperature water through the coffee powder, thus inaugurating the first high-pressure extraction method for espresso coffee. The final result of this innovation translated into obtaining an espresso coffee that differed from the traditional bitter type, lacked the characteristic burnt aftertaste, and was characterized by a dense and creamy consistency. In 1947, Achille Gaggia registered a second patent, introducing the piston and replacing the screw press system with a lever that pushed the water at a pressure of 9/10 atmospheres into the ground coffee. This innovation allowed for the extraction of the aromas that gave the typical fullness to the taste and the components that contributed to the formation of the crema. The coffee, passed through only by the water, fully maintained its olfactory and gustatory characteristics ‘in the cup’. The intense aroma, in particular, contributed to the rapid success of the ‘crema caffè espresso’, consolidating this way of tasting coffee as one of the most famous symbols of ‘Made in Italy’.

Optimal espresso preparation

From a physical point of view, espresso is a beverage with a volume of 25-30 ml obtained by the percolation of hot water under pressure, for about 25 seconds, which passes through a layer of roasted, ground, and pressed coffee (approximately 7-9 g); in passing through the coffee powder, the water pressure (9 atmospheres) is depleted, and the beverage exits at atmospheric pressure. From a chemical point of view, it is a solid-liquid extraction where the solvent is hot water. The espresso method for coffee preparation is distinguished from other methods primarily by the use of high water pressure and a temperature that does not reach the boiling point. Furthermore, the particularly fine grind of the roasted coffee offers a resistance to the percolating water that allows the extraction of lipophilic and water-soluble substances, which give the beverage in the cup unique characteristics in terms of crema, aroma, body, and aftertaste. Of fundamental importance is the freshness of the roasted blend; in practical terms, the maximum fragrance of the espresso is obtained upon opening the manufacturer’s sealed package. As days pass, the exposure of the beans to ambient air tends to cause the oily substances contained to become rancid, resulting in less crema production and alteration of the taste. It is important to highlight that grinding at the moment also has great importance, as 40% of the aromas have already volatilized just 20 minutes later. The cup also has its importance: the conical shape allows for precise observation of the quantity dispensed into it; the thick wall, or large mass, contributes to keeping the espresso temperature relatively constant; the cup must be hot even before use, which is why cups in coffee bars are positioned above the machine, covered by a cloth napkin. In addition to the porcelain cup served with the saucer, espresso coffee is very often served in small glass cups used for consuming spirits like vodka, and is called caffè in vetro (coffee in glass), but this has no influence on the taste of the beverage. In reality, there is a small difference: the glass cup retains less heat, and therefore the coffee cools down faster.

Regarding caffeine, however, there are several factors to consider, depending not only on the coffee variety but also on the grind and the processing method. In the case of the grind, the finer it is, the higher the amount of caffeine will be. The reason is strictly linked to the preparation: the fine blend makes the passage of water more difficult and slower, which allows it to extract more substances, including caffeine. The roasting also affects the amount of caffeine, as does, obviously, the quantity of water used. Espresso coffee has a caffeine content that ranges between 30 and 50 milligrams per 30 milliliters, the equivalent of one small cup, while Americano coffee, for example, contains between 8 and 15 milligrams for the same quantity. Therefore, given the same quantity, espresso coffee has more caffeine than Americano, but upon closer inspection, there is a misunderstanding that needs clarification. When we drink an espresso, we consume only one small cup (about 30 ml, in fact), whereas when we sip an Americano coffee, we consume about 240 ml (1 cup). If mathematics is correct, it is clear that for the same quantity, espresso is richer in caffeine, but in fact, we consume more total caffeine with a cup of Americano coffee.

Weather and climate affecting coffe production and quality

Soil and climate play a crucial role in determining the aromatic and flavour profiles of different coffee varieties. Nutrient-rich soils, such as volcanic ones, strongly influence the quality of the coffee. Such soils are found in regions like Ethiopia or Costa Rica. Coffees grown in these lands often have complex aromatic profiles, with floral and fruity notes. Furthermore, climates, together with specific altitude conditions, further contribute to this rich variety of flavours and aromas. Two main climatic components are to be considered: temperature and rainfall. The ideal temperatures for coffee cultivation are between 18 and 24°C. A temperature that is too high or too low can stress the plants and alter the quality of the coffee cherries. Regions with a marked alternation between distinct seasons—for example, a rainy season followed by a dry period—allow the cherries to ripen slowly. Altitude also plays a crucial role. Coffees grown at high altitudes, such as in Jamaica on the Blue Mountains, are exposed to cooler temperatures. These conditions slow down the ripening of the cherries, thus allowing a greater accumulation of sugars and volatile compounds, which enriches the coffee’s taste profile. Besides global factors, microclimates also play a significant role. A microclimate is determined by climate variations over a restricted geographical area. Local hills, valleys, and water basins can create unique microclimates that influence the sunlight, temperature, and humidity of the plantations. For example, a hillside might receive more sun than an adjacent valley, thus influencing the ripening time of the cherries and the concentration of aromas. Current climate changes can affect coffee production and quality: Higher temperatures accelerate the ripening process of coffee cherries, leading to unbalanced aromatic profiles. Furthermore, the increase in heat raises the proliferation rate of pests, such as coffee berry borers, which incessantly attack crops: a double problem that enormously affects both quantity and quality. Not only that, but marked fluctuations in rainfall also lead to harmful consequences: heavy rains erode the soil’s nutrients, which are essential for plant health, while pest and disease epidemics after prolonged periods of drought increase the difficulties for producers. Likewise, extreme events—unforeseen hail, floods, strong winds—lead to devastating crop losses, adding volatility to an already unstable market, which means a real and alarming risk to satisfy future coffee demand. The search for climate-change-resistant coffee is ongoing. Although the Robusta variety seems less vulnerable, the future of Arabica, which accounts for approximately 70% of world production, is uncertain. Scientists and agronomists are working diligently to identify and develop cultivars capable of facing future climatic challenges.

The most widespread coffee species in the world

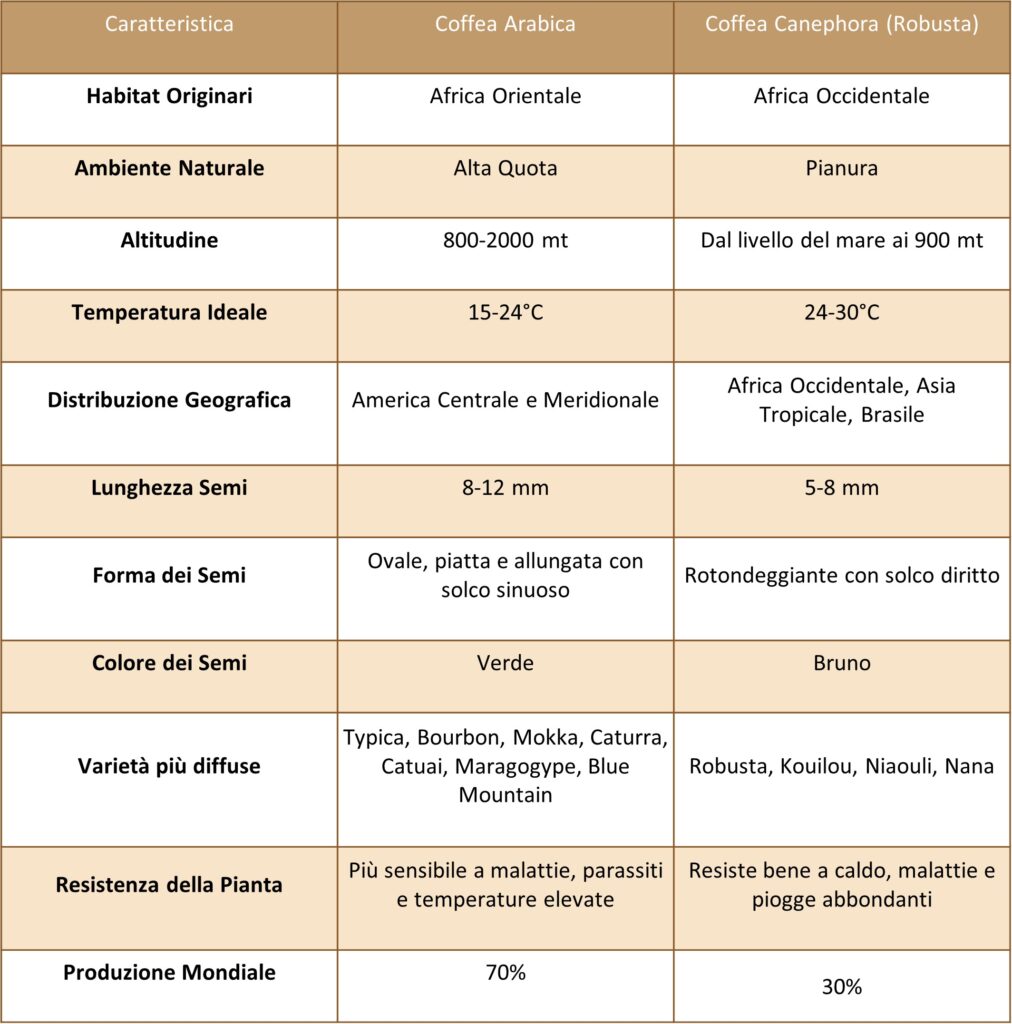

Coffee is produced by grinding the seeds of the tropical tree Coffea, belonging to the Rubiaceae family. Currently, there are almost one hundred species of the plant, but only a few are exploited for coffee production. In particular, the two most used worldwide are:

Coffea Arabica: It is the most known and used, and originates in Africa and Arabia. The coffee produced from this species is described as a beverage with a sweet taste but with a bitter edge and rich aroma.

Coffea Robusta: or Canephora, takes its origins from tropical Africa. These beans allow for the production of a beverage with a more delicate flavour compared to Coffea Arabica.

The Arabica variety of coffee, consisting of $100\%$ Arabica beans, has a higher sugar content than other varieties. This is how this characteristic contributes to its flavour qualities:

- Delicate flavour;

- Light and smooth body;

- Medium intensity;

- Fruity aroma;

- Slightly acidic taste.

Unlike Arabica, the Robusta type of coffee produces a beverage with a completely different taste. Here are its main characteristics:

- Strong and decisive flavour;

- Full and round body;

- High intensity;

- Spicy aroma, with notes of dried fruit and chocolate;

- Slight bitterness.

The main differences between the Arabica and Robusta varieties are: Arabica coffee is particularly appreciated for its delicate, sweet, and aromatic flavour, with fruity notes and a slight acidity. Robusta coffee, on the contrary, has a stronger, bitter, and fuller-bodied taste. While Arabica represents about 60-70% of global coffee production, Robusta covers 30-40%, offering a more intense energy boost.

What are the nutritional properties?

Certamente. Ecco la traduzione in inglese delle proprietà nutrizionali che ha fornito:

🇬🇧 Nutritional Properties of Ground Coffee

On average, 6 grams of coffee powder are used to prepare one cup of coffee. 100 grams of ground coffee (Arabica and Robusta blend) provide approximately 287 Calories and contain roughly:

- Water: 4 g

- Protein: 10 g

- Lipids (Fats): 15 g

- Carbohydrates: 28 g

- Calcium: 130 mg

- Iron: 4 mg

- Phosphorus: 160 mg

- Potassium: 2020 mg

- Sodium: 74 mg

- Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin): 0.2 mg

- Vitamin B3 (Niacin): 10 mg

The caffeine content of coffee depends on the blend (Arabica or Robusta), ranging from 1–2 g of caffeine per 100 g of coffee powder.

A cup of coffee, prepared with about 6 g of powder, typically contains 50 to 120 mg of caffeine, depending on the brewing method (espresso or moka pot) and the blend type.

Positive Effects

- Central Nervous System (CNS) Stimulant: Coffee stimulates the CNS, reducing the feeling of sleepiness and increasing the sensation of well-being.

- Cardio-Psychic Benefits: Its tonic and stimulating effects are also felt on the heart and at the level of psychic functions, leading to improved memory capacity and increased ease of reasoning.

- Digestive and Metabolic Effects: The stimulating effect is also perceived in digestive activity, as it promotes gastric and biliary secretion. Furthermore, coffee reduces appetite and the feeling of hunger.

- Protective Properties: It has significant antioxidant properties and, according to various studies, anti-inflammatory properties. It can also function as an analgesic against headaches.

Negative Effects and Tolerability

- Individual Variation: The tolerability of this beverage varies from person to person.

- Negative Symptoms (Exceeding Tolerance): When the tolerance threshold is exceeded, negative effects can range from palpitations and cardiac rhythm disorders to tremors, insomnia, stomach acidity, and hyperexcitability.

- Potential Health Risks: Too much coffee can also lead to depressive states and hypertension. It can also cause or exacerbate gastritis and gastric reflux.

- Children: Given its neurostimulating action, this beverage is unsuitable for consumption by children.

Caffeine and Cortisol

- Nervine Drink: Coffee is considered a nervine drink because it contains caffeine. This alkaloid acts on the CNS, keeping us awake and providing energy.

- Early Morning Consumption: What is less known is that there is greater caffeine absorption in the first hours of the day. Caffeine acts as a stimulant for cortisol, the stress hormone that affects metabolism, the immune system, and blood sugar levels.

- Best Time to Drink: Therefore, the best times to drink coffee are mid-morning or before physical exertion.

Coffee Variants

Coffee is the most consumed beverage in the world, and countless variants exist, especially in Italy. Below are the main ones.

- Caffè Ristretto (or Short Espresso): This is achieved by simply allowing less liquid to flow into the cup, extracting only the first fractions from the ground coffee powder. The result is a coffee that has intensity, body, and aromatic fineness. It is also denser (creamier), as the crema (foam) constitutes a significant fraction of the total volume in the cup.

- Alternative English term: Ristretto (often used directly), Short Shot.

- Caffè Lungo (or Long Espresso): Obtained by allowing more water to flow into the cup, this results in a coffee with greater dilution. It has a different aromatic fineness due to the greater extraction of substances, a pronounced bitterness, and a higher caffeine content.

- Alternative English terms: Lungo (often used directly), Long Shot.

- Caffè Americano (American Coffee): This is an espresso shot to which hot water is added to make it longer and more dilute.

- A variant is the Long Black, popular in Australia and neighboring areas, in which the cup is first filled with hot water, and then the espresso is poured in.

Caffè Macchiato (known as Cortado in Spain): this is prepared by adding a small amount of milk, either cold or hot, to the espresso. Therefore, the freshly prepared espresso is named macchiato freddo (cold macchiato) or macchiato caldo (hot macchiato).

- Sometimes, only the foam/froth of hot milk or cream is added, resulting in the variants Caffè con Panna (Coffee with Cream) and Caffè Schiumato (Coffee with Foam).

Caffè Corretto (literally, “Corrected Coffee”): This is a common term used to indicate an espresso shot with the addition of a small amount of hard liquor/spirit, which must be specified when ordering. Grappa or Sambuca are typically used. The coffee can be served in the cup (or a small glass) with the alcohol already poured in, or with the alcohol served separately. Recently, it can also be “corrected” with Zabaione (a mix of sweet cream and alcohol), combining a sweet and alcoholic flavor.

Caffè Decaffeinato (Decaffeinated Coffee): an espresso made from ground powder that has been subjected to a process of caffeine extraction before being used to brew the drink.

- Alternative English term: Decaf Espresso.

Caffè Viennese (Viennese Coffee): Popular in the Triveneto region (Northeast Italy), this is an espresso topped with chocolate, whipped cream, and cinnamon or cocoa powder.

Caffè Calabrese (Calabrian Coffee): originating in Calabria, this is an espresso served with licorice, flambéed with brandy or cognac, and a teaspoon of sugar.

Caffè Leccese (Lecce Coffee): The authentic coffee from the Salento region (Puglia) can be simple with ice cubes, or “soffiato” (blown), meaning frothed/whipped for a few moments with steam. The original Lecce variant involves the addition of almond milk, whose very sweet flavor replaces the need for sugar.

- (There is a similar version in Spain known as café del tiempo: hot coffee, ice, and a slice of lemon.)

Caffè “Marocchino”:

Born in Piemonte, this drink has rapidly spread throughout the peninsula and has nothing to do with the African nation. Its original recipe is composed of a base of milk cream and coffee and features a dusting of dark cocoa powder on top. It should not be confused with the Mocaccino, where chocolate is present as an integral part of the beverage.

Caffè Shakerato:

This is a cold beverage prepared with espresso coffee, ice, and sugar, shaken together to achieve a creamy and frothy consistency. It is prepared by pouring the hot coffee into a shaker with the ice and sugar (or syrup) and vigorously shaking for about a minute before serving.

Curious facts about coffee

The coffee plant has green leaves, white flowers, and red fruits, just like the colors of the Italian flag.

The coffee fruit is called a drupe or a cherry, and it is composed of an outer skin, the pulp, a parchment that covers the bean, a silver skin, and the bean itself.

The top five coffee-producing countries are, in order: Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia, and Ethiopia

The most expensive coffee is Kopi Luwak (it can cost over $300/kg!), and it is produced in Indonesia. What makes this coffee so special is the fact that the beans are eaten and digested by the Asian palm civet before being collected from the animal’s feces, then washed and roasted.

It is said that Beethoven was a true perfectionist, even in preparing his coffee: to make the perfect cup, he counted out exactly 60 beans one by one.

It was the participants and supporters of the Boston Tea Party (an act of protest by American colonists against British government taxes) who introduced coffee instead of tea for the five o’clock break. This was a resolute gesture to further reinforce their independence from the British

It is recounted that the French writer and playwright Honoré de Balzac consumed about 50 cups of coffee a day to “fuel his creative flair.

Coffee was declared illegal not once, not twice, but three times! The first time was in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, in 1511. Then it was the turn of Europe in 1675 when, by an edict of Charles II, the operation of coffee houses in London was prohibited, and finally, in Germany in 1777, by an ordinance of Frederick the Great, who was concerned about the economic implications related to importation.

The top 10 per capita coffee consumers in the world are:

| Country | Consumption |

| Finland | 12 kg/year |

| Norway | 9.9 kg/year |

| Iceland | 9 kg/year |

| Denmark | 8.7 kg/year |

| Netherlands | 8.4 kg/year |

| Sweden | 8.15 kg/year |

| Switzerland | 7.9 kg/year |

| Belgium | 6.8 kg/year |

| Luxembourg | 6.5 kg/year |

| Canada | 6.5 kg/year |

And what about Italy? It ranks 13th, after Bosnia (?) and Austria, but ahead of Brazil!

Leave a Reply