Setting foot for the first time on an unexplored land always evokes a certain emotion. If it’s a distant land, unreachable for most of humanity, the last in chronological terms to be explored, and one that even today represents a challenge for human beings, then the emotion doubles, even triples. Antarctica, also known as the South Pole, is one of those less visible points on the globe, far from everything, even dreams.

How many of us, as children, were fascinated by adventurous tales of the conquest of the North Pole, of Umberto Nobile’s expeditions and his airships, the famous “red tent”? It seemed like a mythical, almost unreachable place. Of the South Pole, especially in Italy, there was little news, almost as if it were another planet. Yet, in February 2002, a century had passed since the “landing” on this continent by a famous and intrepid explorer: Captain Robert Falcon Scott of the Royal Navy. Here, ten years later in 1912, he froze to death along with his crew, after losing his personal race to the geographical South Pole against the Norwegian explorer Amundsen. Still, even today, many know little or nothing about this immense white desert, except that it’s the most inhospitable, cold, and isolated land on our planet.

A short history

“…Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell, which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman.”

These are the last words Sir Robert Falcon Scott wrote, fully aware of his impending death, in his diary found beside his lifeless body on November 12, 1912, by the relief expedition. It was the tragic end of a challenge, or rather, a double challenge, both lost: the one against the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen for reaching the geographical pole, and the one against the Antarctic ice. But these two explorers were not the very first to have reached the immense white continent, although in 1901, during Scott’s first expedition, Antarctica was more unknown than the Moon was before the 1969 moon landing. In the 15th century, the existence of a southern continent, connected to the southernmost coasts of Africa and South America, was hypothesized. But Vasco da Gama first, and Francis Drake later, provided proof of its non-existence. However, the conviction of a land further south remained alive in some circles. It was in 1773 that James Cook first crossed the Antarctic Circle, then blocked at 71° South latitude by an impenetrable ice barrier. We have to wait until 1819 for someone else to venture to those latitudes. It was William Smith, while rounding Cape Horn, who, driven by a storm, reached the first sub-Antarctic islands, which he christened the New South Shetlands, today the South Shetland Islands. On another voyage, driven further south by another storm, he sighted the outline of the mainland; he had glimpsed the long-sought continent: it was the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula! From that moment on, the true explorers of Antarctica were English seal hunters, such as James Weddell and John Balleny, drawn to those seas by the abundance of prey. In 1820, Thaddeus von Bellingshausen was the first to glimpse the outline of the Antarctic continent with an expedition financed by Tsar Alexander I of Russia. Between 1837 and 1839, there were three simultaneous expeditions in search of the magnetic South Pole: the American one led by Charles Wilkes, the French one by Dumont d’Urville, and the English one by James Clark Ross, who had already been the first to reach the magnetic North Pole. Dumont d’Urville was an officer of the French navy, who sailed from Toulon with two corvettes, the Astrolabe and the Zelee. After years of navigation, in 1840, he landed on a small rocky island near the mainland, home to a colony of Adelie penguins; that island is now the site of the French base.

Two years later, Ross, with his two ships, the Erebus and the Terror, sighted the Antarctic land—precisely the part of the continent where Italian and American contingents operate today. He began naming territories and mountains: the first majestic cape after Viscount Adare, the first large volcano encountered after Minister Melbourne, and he dedicated all those lands to the young Queen Victoria of England. On January 28, 1841, he arrived at the island that now bears his name, where two majestic volcanoes reigned—one active, the other not—which he named after his two ships (Erebus and Terror, respectively). The stretch of sea protected from the winds by Ross Island was named after the lieutenant of the Terror, Archibald McMurdo (the current location of the American base). Ross finally departed in February 1843, having pushed further south than all his predecessors: to 78°10′ latitude. He couldn’t go beyond that point, hindered by the massive presence of eternal ice; the only way to penetrate further into the continent was to land on the ice, a risky and unappealing endeavor.

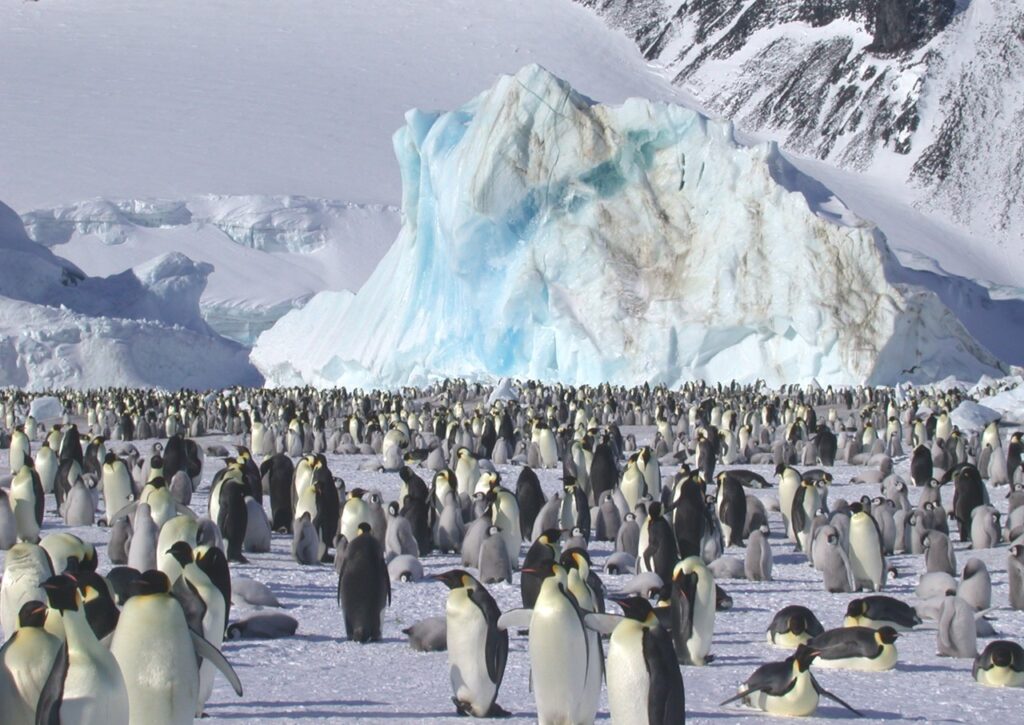

Fifty years passed before another expedition ventured to the continent Americans call “THE ICE.” In January 1895, a Norwegian, Borchgrevink, and his companions made the first landing in Antarctica, coming ashore near Cape Adare. With another expedition he organized, in 1899, the first men (10) were left to winter on that continent. In January 1900, this expedition pushed even further south, to Ross Island; Borchgrevink, using sledges, reached 78°50′ latitude, the southernmost point ever touched by man. The race to the South Pole had resumed. Between 1901 and 1904, there were the first expeditions of Scott and the German Erich von Drygalski. Aboard the ship Discovery, Scott, along with Shackleton, reached McMurdo Sound where he built a wooden base. He spent about two years there, undertaking a series of sledge traverses across the Ross Ice Shelf and around McMurdo to deepen their knowledge of the area. Much meteorological, biological, geological, and geophysical data was collected, and he reached the southernmost point ever attained by a human. Drygalski, with his ship Gauss trapped in the pack ice, conducted numerous meteorological observations with hot-air balloons and a careful study of the life habits of seals and penguins. Other expeditions followed, which, in addition to having a scientific purpose, aimed to get ever closer to the geographical South Pole. In 1908, Shackleton came within just 180 km of this geographical point; in 1909, Edgeworth David and Douglas Mawson reached the magnetic South Pole.

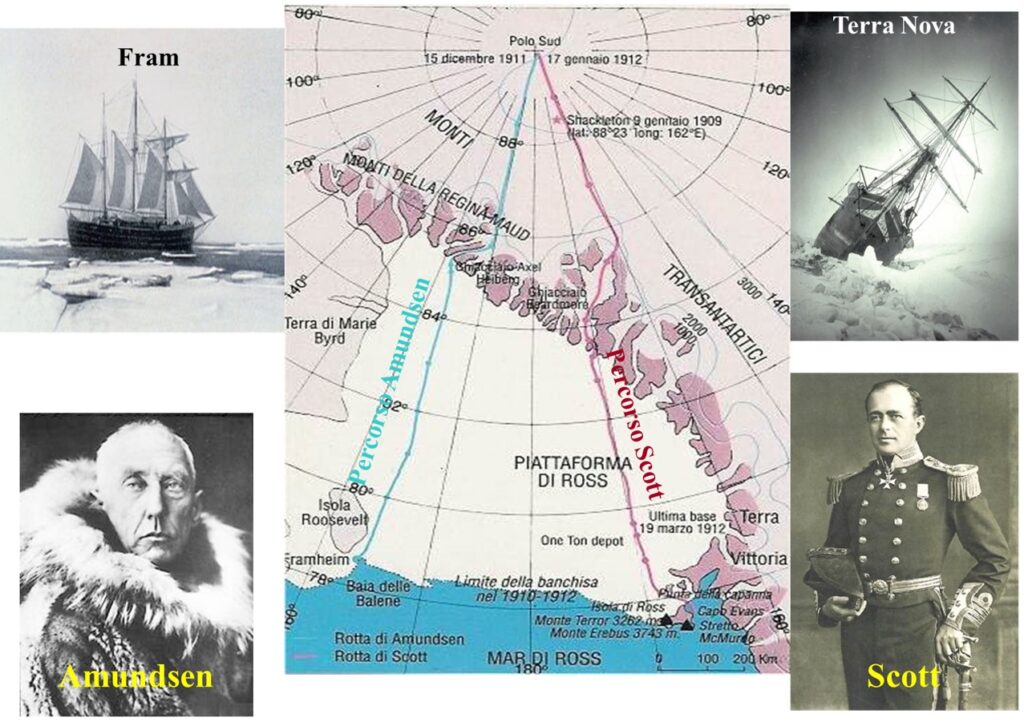

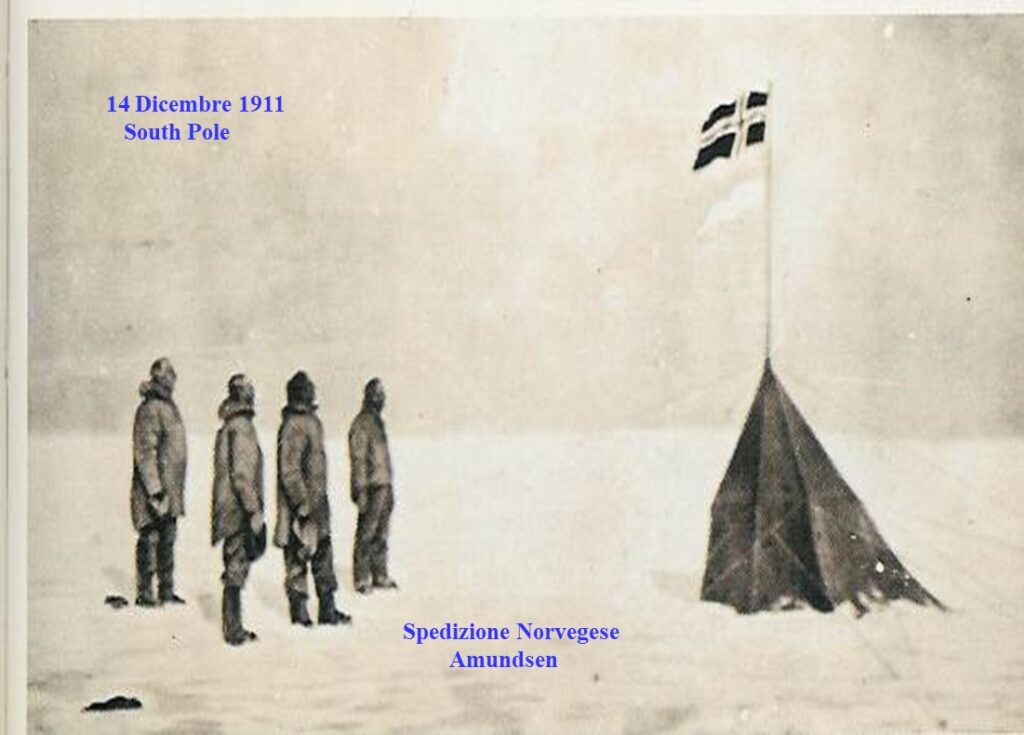

Then, in the austral summer of 1911-1912, the final act of this race for supremacy unfolded. On December 14, 1911, the Norwegian Amundsen was the first to reach the South Pole, preceding the British Scott and his four men by about a month (January 17, 1912). However, Scott’s expedition would have a tragic end. On the way back, Evans and Oates perished, and about 160 km from their starting base and just 17 km from the “One Ton Depot” supply base, Scott himself and his other two companions, Bowers and Wilson, also lost their lives.

The books on this race to the South Pole are incredibly interesting reads: “The Worst Journey in the World” (the full translation of Scott’s diary), “The South Pole” by R. Amundsen, and “The Race for the South Pole” by R. Huntford. In 1915, Shackleton attempted to traverse the continent from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea. Although the expedition failed from the outset, it wrote another heroic page in the discovery of this continent. His ship, the Endurance, became trapped in the ice of that sea. However, after various hardships, Shackleton managed to reach South Georgia in a lifeboat and organized a rescue expedition that saved the rest of his crew (you can read about this in the book: “South: The Story of Shackleton’s Last Expedition, 1914-1917“). In 1928, Wilkins made the first flight over the Antarctic continent, but it was Byrd in 1929 who first flew over the South Pole. In 1935, the first woman set foot on Antarctic soil: Mrs. Caroline Mikkelsen, the wife of a Norwegian captain.

Thereafter, missions continued with increasing frequency, leading to the establishment of various bases by many nations. Among these, since 1985, Italy has also been present, thanks to the National Antarctic Research Program (PNRA), established by law in June of that year (Law No. 284 of 10/6/85).

A Look at the White Continent

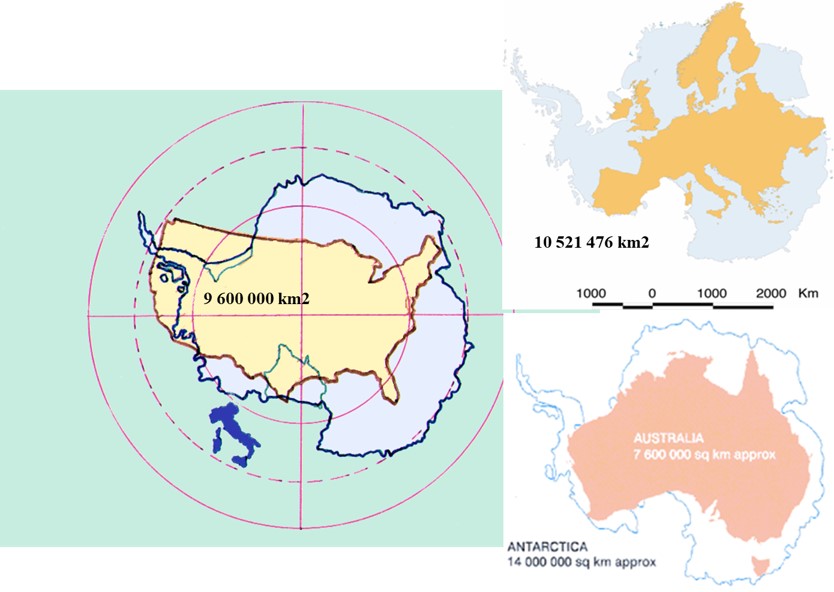

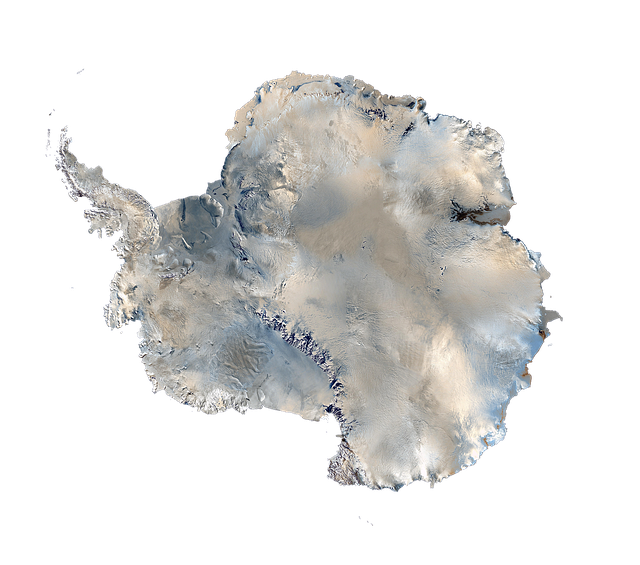

Antarctica, more commonly known as the South Pole, is an immense white continent. Its size is one and a half times that of the European continent, measuring 14 million square kilometers. It’s located in the Southern Hemisphere and can be considered an enormous glacier resting on land, not on water, as is the case with the opposite pole, the Arctic (or North Pole). During winter, the area of sea ice surrounding the mainland is larger than the continent itself, averaging about 20 million square kilometers.

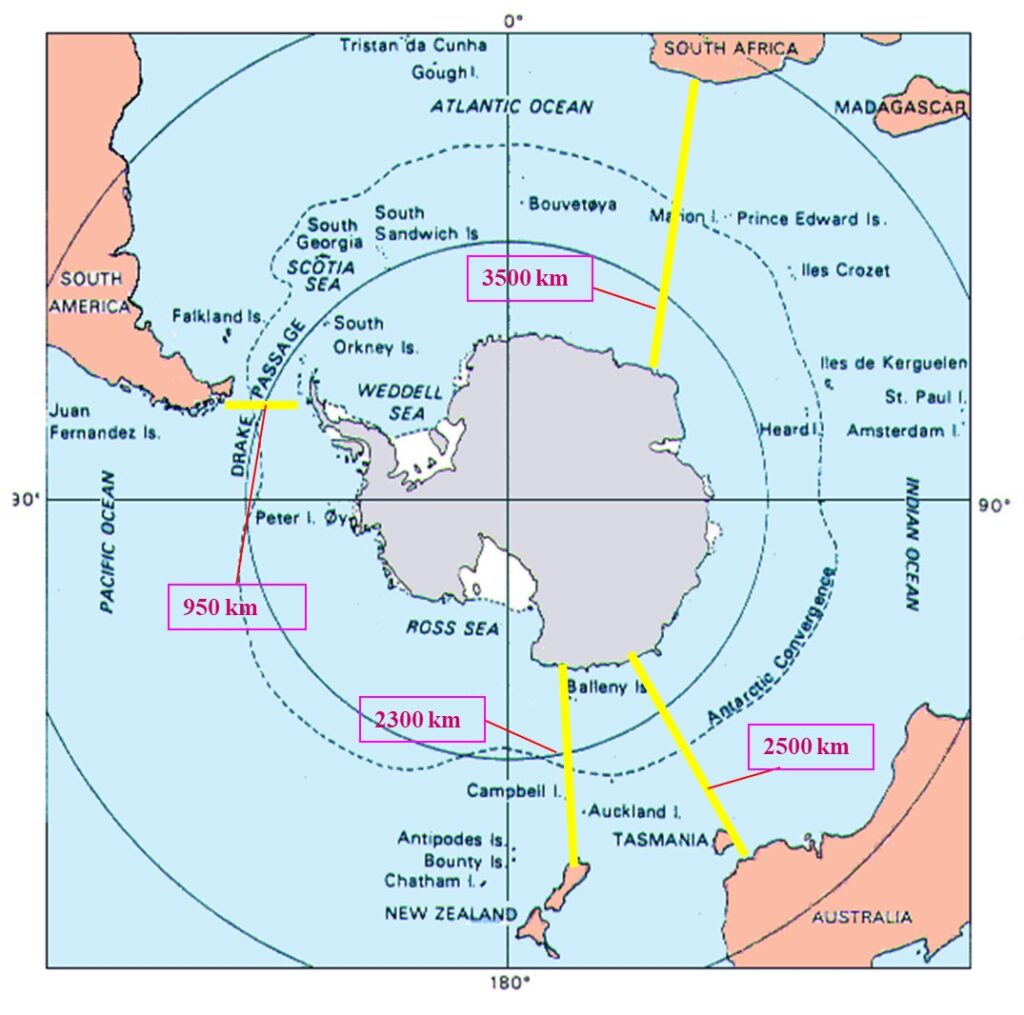

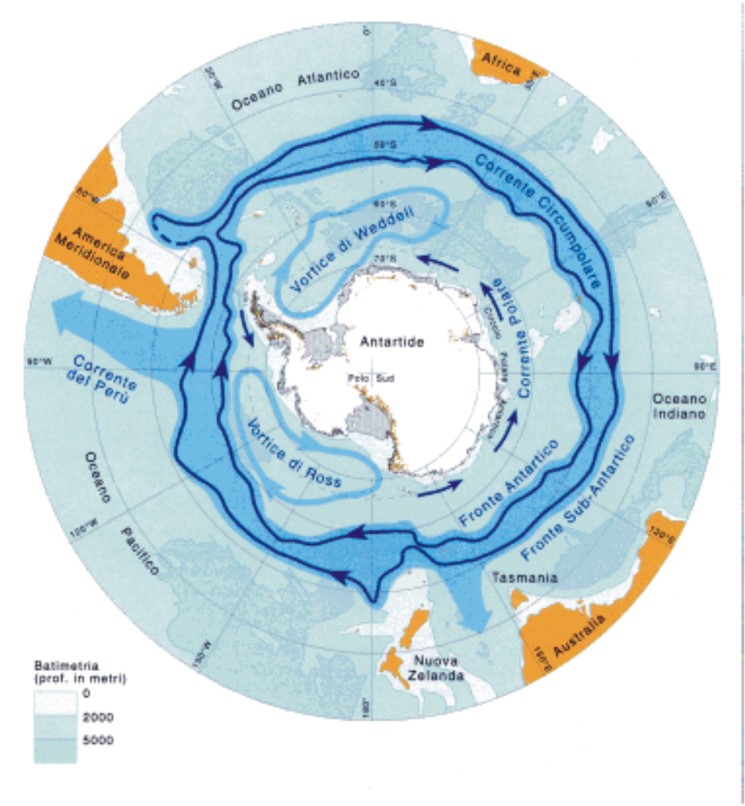

Being entirely surrounded by the three oceans (Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic), both its oceanic and atmospheric circulation are almost isolated. This means energy exchanges with the “outside world” occur on a larger timescale, or more slowly than elsewhere. This “isolation” is better understood when we consider that the closest point to another landmass is “just” 950 km away, which is the stretch separating the Antarctic Peninsula from South America. It’s then 2,300 km from New Zealand, 2,500 km from Australia, and 3,500 km from South Africa.

The derivation of the names for the two poles, Arctic and Antarctic, is quite unique. The ancients, to locate north, followed the North Star, which is the first star in the constellation Ursa Minor, or Arktos in Greek (hence “Arctic”). Therefore, the antipolar position relative to the north was designated as Anti-Arktos, leading to the current name Antarctica. It can be considered the 6th continent and is larger than Europe, Australia, and the USA.

Here are some numbers:

Antarctica has the coldest climate on Earth, but also the driest (even more so than the various deserts found in tropical zones). It’s easy to understand why the poles are cold: their geographical position means that sunlight strikes at a very acute angle, resulting in less “heating power.” Added to this is the fact that they’re covered by a layer of ice of varying thickness (naturally, thicker in Antarctica), which acts like an enormous mirror, reflecting much of the incoming solar radiation back into space.

Unlike the Arctic, Antarctica is primarily landmass, not just sea, covered by ice. This allows for greater heat dissipation. It has an average elevation of 2,500 meters, making it the highest continent on Earth (Asia, ranked second, has an average of 900 meters), with mountain ranges exceeding 4,000 meters.

The transition from the summer to the winter season, which occurs at opposite times compared to our hemisphere, is characterized by an increase in daylight hours, a significant change in temperatures, and a variation in the extent of sea ice. This ice ranges from a minimum of about 16 million sq km in the peak summer to a maximum of about 32 million sq km, typically observed in September. During the thaw, a massive amount of water forms. Being denser and colder than the surrounding water, it sinks and feeds deep ocean currents, thus influencing the ocean’s general circulation.

It’s more challenging to grasp why Antarctica is considered the “king” of deserts. How can such an immense ice-covered land be a desert? In geography, a desert is defined as an area of the Earth’s surface that is almost or entirely uninhabited, where precipitation rarely exceeds 250 mm/year, and the ground is predominantly arid with sparse vegetation. If this term primarily indicates locations characterized by low precipitation, then it must be stressed that the South Pole experiences even lower precipitation regimes than the Gobi Desert and the Sahara – it’s just much, much colder at the pole! To give you an idea of the precipitation in this remote part of the world, the average value across the entire continent is around 130 mm/year (less than the rainfall during the Piedmont flood), with a maximum of 500 mm/year on the Antarctic Peninsula and a minimum of 30 mm/year in the interior zones (Plateau).

The climate is essentially dry, and even if the relative humidity can exceed 80%, the water vapor content in the atmosphere is very low compared to what’s found at our latitudes. This immediately highlights a natural “contradiction”: the world’s largest freshwater reserve is actually a vast desert! Indeed, water is present in enormous quantities, but in the form of ice, and therefore, in fact, scarcely available in liquid form.

We’ve established that it’s also a very cold continent, indeed the coldest, with extremely low temperatures on the Plateau during the austral winter. The lowest temperature recorded by a weather station was -89.2 °C, noted at the Russian Vostok research station on July 21, 1983. However, based on satellite data, scientists announced in 2013 that they had detected the lowest temperature ever recorded on our planet in the East Antarctic Plateau: -93 °C in the winter of 2010. Following a re-examination of meteorological data from that region, researchers found that temperatures in several spots dropped even further, reaching as low as -98 °C. The analysis of this data was published in Geophysical Research Letters

If, within the framework of global climatology, Antarctica is part of the polar climate zone, its interior, despite the generally low temperatures, can be divided into no fewer than four distinct climatic regions:

- Antarctic Plateau: This region is characterized by weak winds, scarce snowfall, predominantly clear skies, and extremely low temperatures.

- Slope Zone: Here, the plateau slopes, more or less steeply, towards the ocean. It’s marked by strong katabatic winds (a term derived from a Greek word meaning “descending”), blizzards, and more abundant precipitation than on the Plateau. This is where the wind chill effect can be most elevated due to the action of the winds.

- Coastal Zone: Temperatures here are “higher,” humidity is greater, and it’s particularly affected by the sea, especially during the thaw period. During this time, the coastal zone experiences the highest precipitation due to the sharper contrast between the cold, dry air from the plateau and the more humid, less cold air from the sea. This area is also most affected by the passage of disturbances forming along the subpolar belt. The action of katabatic winds is significant here as well, sometimes even more intense than in the slope zone, largely depending on the “flow paths,” or the local topography. The Italian base experiences this type of climate.

- Maritime Region: This zone is limited to a part of the Antarctic Peninsula, specifically its northernmost section. Its weather is heavily determined by the passage of circumpolar disturbances (those that move around the continent). Temperatures are higher, not only due to its more northerly latitude but also because it’s surrounded on three sides by the sea. Precipitation is also more abundant.

The winds in this part of the world, among the windiest on Earth, are quite unique and intense, strongly influencing the possibility of survival on the white continent. We know that wind has a high cooling power, so much so that the body perceives a temperature different from the actual air temperature when wind is present: this is the well-known wind chill effect, which is proportional, though not linearly, to the wind’s intensity. The most characteristic and intense winds are the so-called katabatic winds, caused by the movement of colder air masses that “slide” from the Plateau towards the ocean, often wedging themselves between glaciers. These winds often reach 170-180 km/h, sometimes exceeding that threshold to hit 230-250 km/h. These cold air masses are set in motion by two main factors:

- A powerful stratospheric flow pushing them downwards from above towards the edges of the Plateau.

- The classic circulation driven by the contrast between high-pressure zones situated over the Plateau and the deep low-pressure systems that, especially in the summer, move near the Antarctic coasts.

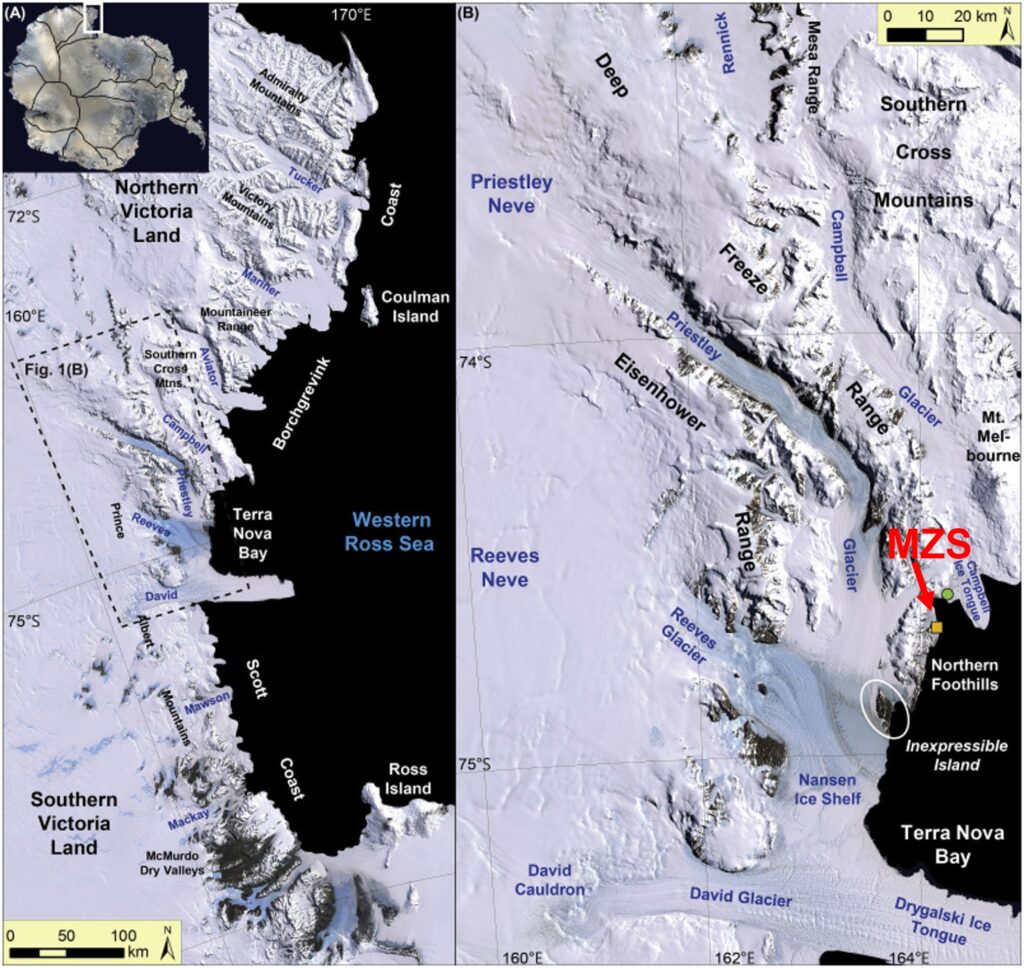

The Italian base (Mario Zucchelli Station) is located on the coast in an area significantly affected by this phenomenon. It has three nearby glaciers that act as preferential pathways for these air masses to flow: the Campbell, the Priestley, and the Reeves glaciers.

Mario Zucchelli Station (MZS): Italy’s Gateway to Antarctica

The Italian research station, initially known as BTN (Baia Terra Nova), was renamed Mario Zucchelli Station (MZS) in 2005. This decision honored the memory of engineer Mario Zucchelli, who for many years led the National Antarctic Research Program (PNRA). The station is located at 74° 41′ 42″ S, 164° 7′ 23″ E, 17 meters above sea level, on a promontory extending into the small Gerlache Inlet, which is part of the larger Terra Nova Bay. The nearby Northern Foothills provide natural protection from western winds, particularly the powerful katabatic winds that sweep violently from the Priestley and Reeves glaciers, occasionally reaching the base. The Priestley and Reeves glaciers have distinct morphological characteristics, though both flow into the Nansen Ice Sheet, a glacial valley just a few kilometers from the base. The Priestley Glacier serves as an “access route” to the Plateau via a narrow (8 km) and long (90 km) corridor extending in a SE-NE direction. The Reeves Glacier, while shorter, is much wider (15 km wide and 35 km long) and runs along an E-W axis.

Two other significant glaciers in the vicinity terminate directly into the sea: the nearby Campbell Glacier (120 km long and 5-10 km wide, with an ice tongue extending an average of 18 km into the sea, 5 km wide, and 380 meters thick from sea level) and the more distant but immense Drygalski Glacier (23 km wide, 36 km long, and with an ice tongue 70 km long, 14-24 km wide, and approximately 300 meters thick from sea level). These glaciers are vital for understanding the local environment and the powerful forces of Antarctic nature around MZS.

Right in front of the base stands one of the highest Antarctic volcanoes (around 2,700 meters), whose presence gives the area an appearance that might recall the Bay of Naples… in an ice age.

In this environment, as one can imagine, weather conditions are fundamental for every type of activity, whether scientific (predominantly carried out by air or sea) or logistical. This is why they are highly considered. From this reality stems the need for a service that, beyond playing a crucial role in operational planning, ensures the necessary meteorological assistance for effective and safe execution of these activities.

Italy’s commitment to Antarctic research is showcased through its two primary scientific bases: the Mario Zucchelli Station (MZS) on the coast and the high-altitude, joint Italian-French Concordia Station on the Antarctic Plateau.

Mario Zucchelli Station (MZS)

Construction of what was then known as BTN (Baia Terra Nova) began during Italy’s second Antarctic expedition (1986-1987) and became operational during the fourth expedition (1988-1989). Over the years, the base has expanded with additional modules. Today, the covered spaces of the main building and satellite units total 7,500 square meters. These facilities include accommodations, offices, dining and leisure areas, a medical infirmary and first aid post, laboratories, warehouses, and various plant systems.

Beyond equipped laboratories for chemical, biological, geological, and electronic analysis, MZS also boasts a computing room and an aquarium. The station is home to an astronomical observatory and other permanent observatories dedicated to studying terrestrial magnetism, the ionosphere, seismic movements, tides, geodetic references, and meteorological variables. A central control room coordinates all ongoing operations, both local and remote.

Concordia Station: A Frontier of Climate Research

Italy also operates at the Concordia Station, a joint Italian-French base built on the Antarctic Plateau. Located at Dome C, an elevation of 3,230 meters above sea level, Concordia is exceptionally isolated: approximately 1,000 km from the coast, over 1,000 km from both the Italian Mario Zucchelli Station and the French Dumont d’Urville Station, and 1,670 km from the geographic South Pole (coordinates: 75°06’ S, 123°20’ E).

Construction of Concordia began in 1998 and was completed in 2004. The station has been continuously operational since 2005, even through the frigid austral winter when temperatures can plummet to -80°C. It’s a geographically isolated location with an ice thickness exceeding 3,000 meters, and its climate is comparable to that of the Sahara Desert, characterized by dry air and almost no precipitation.

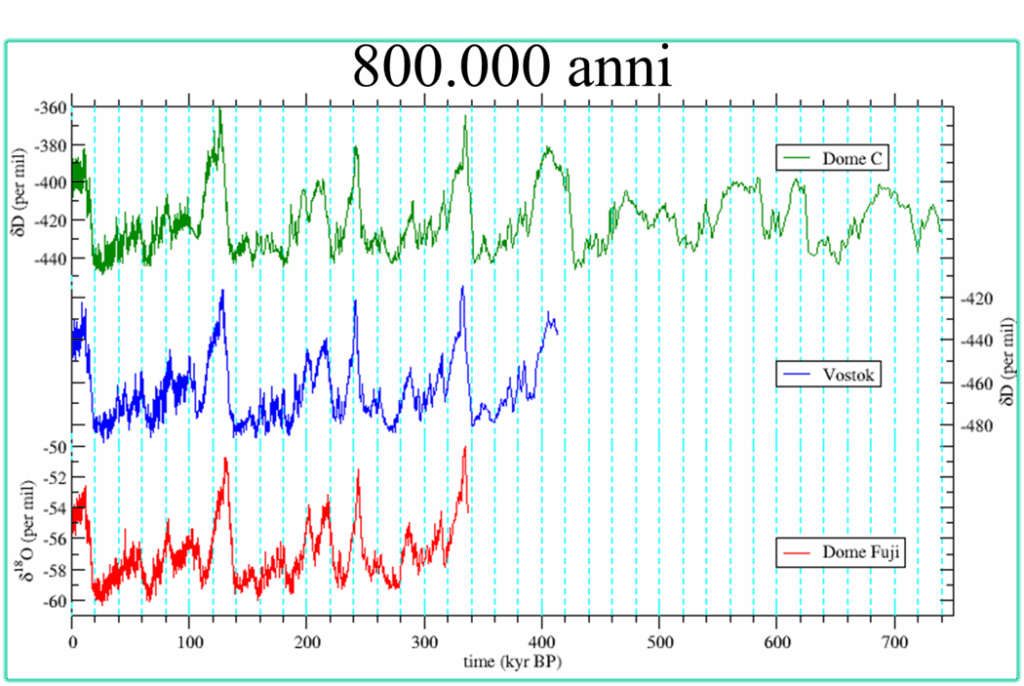

At Concordia, a major climate change study is underway. This research began with the EPICA project and continues with the Beyond EPICA – Oldest Ice project, which aims to extract the Earth’s oldest ice core from the Antarctic ice sheet. The goal is to study this core to gain invaluable information about Earth’s climate dating back over 1.5 million years. To date, ice cores providing climate data from approximately 800,000 years ago have already been extracted from this site.

Concordia Station: A Hub of Antarctic Research

The Concordia Station stands as a remarkable feat of engineering and human endurance in the heart of the Antarctic Plateau. It’s composed of two cylindrical buildings connected by a covered walkway.

Each cylinder measures 18.5 meters in diameter and 11 meters in height, featuring three floors that offer a total usable surface area of 250 square meters. The entire structure rises over 14 meters from the ice, as each building rests on six large, adjustable iron legs. These adjustable legs are crucial for compensating for variations in ice thickness, ensuring the station remains stable despite the dynamic environment.

During the austral summer, from early November to the first ten days of February, Concordia can accommodate up to 34 technicians and researchers. After this summer season, a smaller group, known as the “winter over,” typically around 16 individuals, remains in complete isolation for nine long months. These dedicated scientists and support staff continue research activities through the harsh polar winter, only leaving the station with the arrival of the next expedition in November.

My Missions to Antartica

Various circumstances led me to this immense white continent in the professional role of a meteorologist. I still remember the thrill of my first time there; it felt like living a dream. It was 1998, and the long-awaited news finally arrived: I would be part of the military personnel employed in the 14th expedition. On that occasion, I’d be briefly employed, only for the second period (December to mid-January of the following year), right in the middle of the austral summer.

And so, in 36 hours, I traveled from the cool of Rome to the warmth of Christchurch, New Zealand – a charming New Zealand city known as the “Gateway to Antarctica” since flights depart from here to the Ross Sea area of the continent. We were greeted by a light drizzle, typical of the English climate. After a 24-hour wait, I was finally heading toward my dream: Antarctica.

It was a seven-hour flight over the ocean, with clouds obscuring the view below. We passed an imaginary point, with an ominous and unsettling name: the PNR (Point of No Return). At this point, the aircraft would no longer be able to return to New Zealand, and therefore had to continue to its destination, regardless of the weather conditions. Then, suddenly, the first glaciers and mountains appeared. In that moment, I believe I understood what the Apollo 11 astronauts felt approaching the Moon, albeit in a more subdued way than their experience. Nearby, I had people familiar with this experience who described the places I was seeing. But I was as if frozen by the beauty of the place, by the whiteness of the snows, by the apparent lack of any form of life, and by the opportunity to set foot in a place where no other human being had ever trod before me.

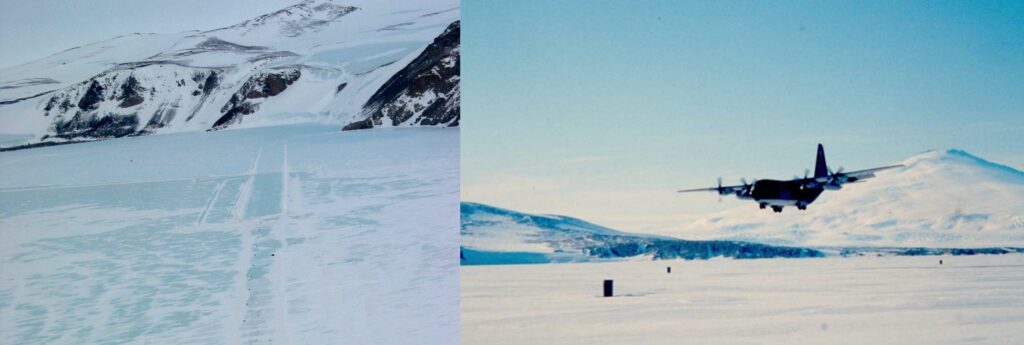

Landing on the ice pack, which is frozen sea, I was walking on a vast expanse of ice that, in a few days, would break apart. The water beneath was 40 meters deep and more. The light was blinding, and visibility was unlike anything I’d ever experienced: places 40-50 km away seemed only a few kilometers distant. I thought that perhaps even our ancestors in ancient Rome didn’t have air this clear. But that expedition was far too brief. Before I could truly grasp where I was or understand the mechanics of the local weather phenomena, the experience was over. With a different spirit, three years later, I embarked on the 17th Italian expedition to Antarctica. Despite the traditionally “unlucky” number, this expedition achieved significant scientific results. These accomplishments weren’t just due to the scientific merit of the various research groups, but also the ability to harmonize, in near-perfect balance, the efforts of every individual involved in the campaign. In this synergy of efforts, we shouldn’t forget the work of those in uniform, who serve as guides across the ice, operators on and under the water, air traffic controllers, and, crucially, weather forecasters. This last role is particularly important in an extreme environment like Antarctica, because it’s thanks to reliable forecasts that operations can be best planned and the highest number of positive outcomes achieved. This involves considering the varying operational capabilities of the transport vehicles used in Antarctica (helicopters, C130s, Twin Otters) and the sudden weather changes, as well as the rapid breakup of the ice pack where the airstrip is built in the early months of the expedition.

I conclude this article with a few photos, some personal, of a place that has stayed in my heart. And who knows, maybe I’ll manage to return there one more time.

Leave a Reply