Wine is a story of love and passion, embracing humanity and spanning millennia of history. Over the centuries, it has played a part in tales of love and friendship, has been the protagonist of cultures and peoples, has inspired poets, artists, and scientists, becoming a shared cultural heritage. The history of wine is lost in the mists of time, to the point that its discovery is shrouded in myths and legends. For example, according to the Bible, the discoverer was none other than Noah, who planted the first vineyard after the Great Flood; for the Greeks, however, it was the God Dionysus, also known as Bacchus to the Romans, the true founder of wine. However, its invention is probably older than we think and is closely linked to the cultural history of ancient civilizations of the past. The vineyard and wine have therefore been an important part of societies since Antiquity, intimately associated with their economies and traditional popular culture. Wine is synonymous with festivities, drunkenness, conviviality; it has imbued itself with a vast field of symbolic values and is present even today in most countries. Its existence is the result of a long and uninterrupted tradition. Probably, wine originated by chance, when some grapes were forgotten in open containers or holes in the ground and began to ferment naturally. It may have been the first peoples of Mesopotamia, more than 10,000 years ago, who experienced this first alcoholic fermentation. Certainly, as manuscripts testify, the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans knew the vine and perfected and developed the production technique. Despite all these suppositions, scholars are currently still unable to define a starting date and indicate an inventor. In this article, we will embark on a rather long journey through the history of wine, starting right from its origins. The oldest traces that speak of grapes intended for wine production date back about 7,000 years ago in the Caucasus, a long strip of land that includes present-day Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Archaeologists have found here the oldest fragments of old vessels used to produce wine, and have therefore decided to consider this land as the mother of grapes and consequently of wine. In all probability, however, the first peoples of the Fertile Crescent had already experimented with the fermentation of grapes, probably accidentally abandoning some ripe grapes in a natural container that surprisingly fermented spontaneously, giving rise to the first ancestor of wine. Certainly, among ancient civilizations, such as the Sumerians and Egyptians, wine was known and used also in religious rituals as an offering to the deities. In particular, the Egyptians had also developed an advanced knowledge of viticulture and winemaking. Vineyards grew along the banks of the Nile River; presses for extracting grapes and sealed resin containers for storing wine have been found. With the rise of the Greeks and Romans, wine assumed an increasingly central and significant position, particularly in the social and religious spheres. It soon became synonymous with celebration and pleasure, also entering people’s daily lives. Obviously, wine was not like that of modern times, but it was often flavored with herbs, spices, honey, or even mixed with other beverages. These peoples were the first to significantly export wine, but above all, the first to plant the vine in new fertile lands, including our very own Italy.

From wild vine to cultivated vine

The domestic vineyard and all traditional vine varieties originate from the wild grapevine Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris, which is a type of climbing Vitis vinifera that grew at the edges of forests. It is still very widespread today in the region between the Caspian Sea and the Atlantic Ocean on the European continent, throughout the Mediterranean basin except for North Africa. This wild vine was already present during the Quaternary period (2.58 million years ago), but it is believed that with the various successive glaciations, it may have ‘taken refuge’ in the Caucasus region, but perhaps also elsewhere. In fact, according to available data from paleobotany, during the Würm glaciation (125,000-11,430 years ago), the main European refugia were the Iberian Peninsula, the Italian Peninsula, and the Balkan Peninsula. Very quickly at the end of the last glaciation, the wild vine recolonized much of Europe. The wild vine appeared before Homo sapiens and is still present in European territory, especially in the alluvial forest remnants of the Rhine Valley. During the 19th century, excavations in the travertine of the municipality of Sézanne revealed the presence of fossils of a vine from the Tertiary era (the Paleocene, 66-56 million years ago) which was named Vitis sezannensis. This variety, which disappeared from European regions due to the Riss glaciation (370-330,000 years ago), survives today in the Southeast of the American continent, but is completely unsuitable for winemaking. The history of the grapevine merges with that of the Mediterranean basin. More than a million years ago, grape varieties were already growing in their wild, uncultivated form; these wild lineages bear only a very distant resemblance to our modern grape varieties.

| Quaternary (2,58 millions of years ago) | The wild grapevine is found to be present on the European continent. |

| Würm glaciation (125.000-11.430 years ago) | The grapevine takes refuge near the Caucasus region, but perhaps also elsewhere. |

| after Würm glaciation | The wild grapevine recolonizes much of Europe, from the Caspian Sea to the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean; the entire Mediterranean basin with the sole exception of North Africa. |

| 8.000 a.C. | Early traces of Vitis vinifera sylvestris: vineyards and wild grapevine in Georgia and the Caucasian territory. |

| 6.000 a.C. | “Appearance of the grapevine from the southern Caucasus to Mesopotamia. |

| 3.000 a.C. | The grapevine is cultivated in Ancient Egypt and Phoenicia. |

| 2.000 a.C. | Appearance in the Archaic period of Ancient Greece. |

| 1.000 a.C. | The grapevine is cultivated on the Italian peninsula, in Sicily, and in North Africa. |

| 1.000-500 a.C. | Appearance of the grapevine in the Iberian Peninsula and in the Midi. |

| 500 a.C. | Middle Ages: Plantings in Northern Europe under the influence of the Roman Empire, reaching as far as the shores of modern-day Great Britain. |

The origins

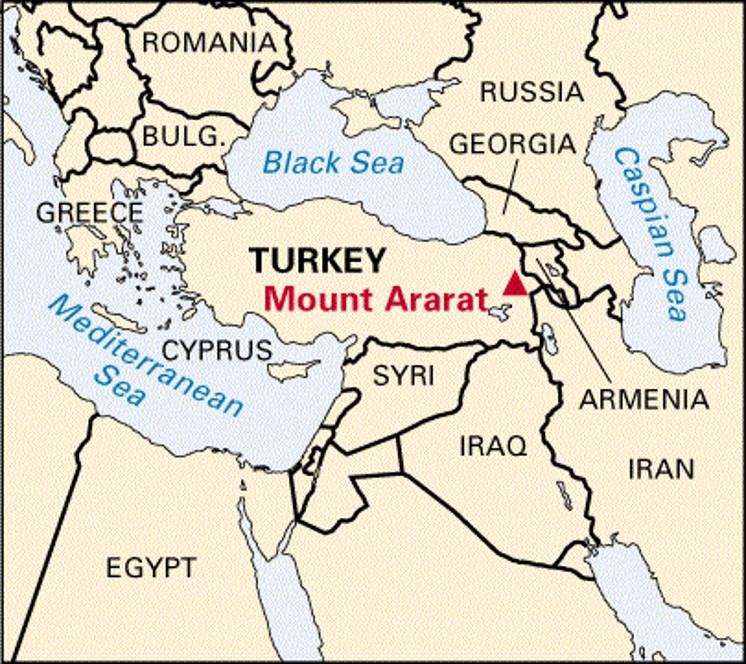

There are countless foundation myths that narrate the constitutive event of the first cultivation of the vine and its fermentation. It has been established that the ancient Greek word οίνός (oinos), which would become “vinum” in Latin through the intermediary of the Etruscan language, belongs to the Indo-European language family and dates back to the root “wVn“; it would be “inu” in Akkadian, “wiyana” in Hittite, and wo(i)no in Mycenaean Greek. The Semitic languages would have borrowed it in the form “wain“, from which “yin” in Ugaritic and “ynn” in Hebrew derive. The ancestral origin of the term is most likely Anatolian-Caucasian; precisely where, on the slopes of Mount Ararat, the text of the Bible places the location where the first grapevine in history was planted. First and foremost, the Book of Genesis 9:20, which mentions the production of wine after the Great Flood, when Noah appears drunk before his sons.

However, the origins of wine predated the history of writing, and contemporary archaeology is still uncertain about the details of the initial cultivation of the wild grapevine. It has been hypothesized that primitive humans gathered the spontaneous clusters and, finding their sugary taste pleasing, habitually began seasonal harvesting. A few days after harvesting, the process of alcoholic fermentation begins, whereby the juice at the bottom of any container starts to produce low-alcohol wine. According to this theory, things began to change around 10-8,000 BC with the transition from a predominantly nomadic lifestyle to a form of ‘sedentarism,’ which led to the birth of agriculture and wine production through the targeted cultivation of vineyards. The production of alcoholic fermented beverages most likely dates back to the Mesolithic period (10,000 BC), if not even the Upper Paleolithic (40,000 years ago); among these, mead was obtained very easily, and its production would appear to be earlier than that of wine. It is generally accepted that winemaking existed for several millennia before the process of selection and cultivation of the vine by humans; this would therefore have allowed Neolithic humans to taste wine. Wild grapes grew throughout the Caucasus region, from Armenia to Georgia, Azerbaijan, up to the northern Levant, the southeastern coastal area of Anatolia, and northern Persia. The fermentation of the strains of this primordial Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris (the ancestor of the modern grape, Vitis vinifera) would have become easier following the development of ceramics after the Neolithic Revolution period (around 11,000 BC). The results showing the oldest winemaking are the results of chemical analyses carried out on deposits found inside vessels at the ‘Hajji Firuz Tepe’ site in Western Azerbaijan. Viticulture subsequently spread to other sites in Greater Persia and Macedonia around 4,500 BC. The Greek site is of considerable importance for the discovery of the remains of macerated grapes. Based on the most recent archaeological discoveries, Armenia has been identified as the ‘homeland of the grape,’ but some scholars point out that this place of origin of the vine was cultivated, as mentioned, together with the region of Mount Ararat. In 2007, a site near the Arpa River near Areni (a village still renowned for its wine production, a mountainous area in southeastern Armenia) was discovered, and inside a cave, vessels full of grape seeds were found, probably dating back more than 6,000 years, and if so, it would be the oldest site where a winemaking operation took place. The Vitis seeds from the Armenian cave are those still used today to make wine and predate the first known comparable wine, found in the tombs of Ancient Egypt, by over 900 years. It would therefore appear that the birthplace of wine seems to have been an Armenian cave. Evidence of trade in both wine and seeds of ancient vineyards has also been found between the Armenian area and present-day Iran, and from there to Palestine, where evidence dating back to 3700 BC has been found.

And the story continues…

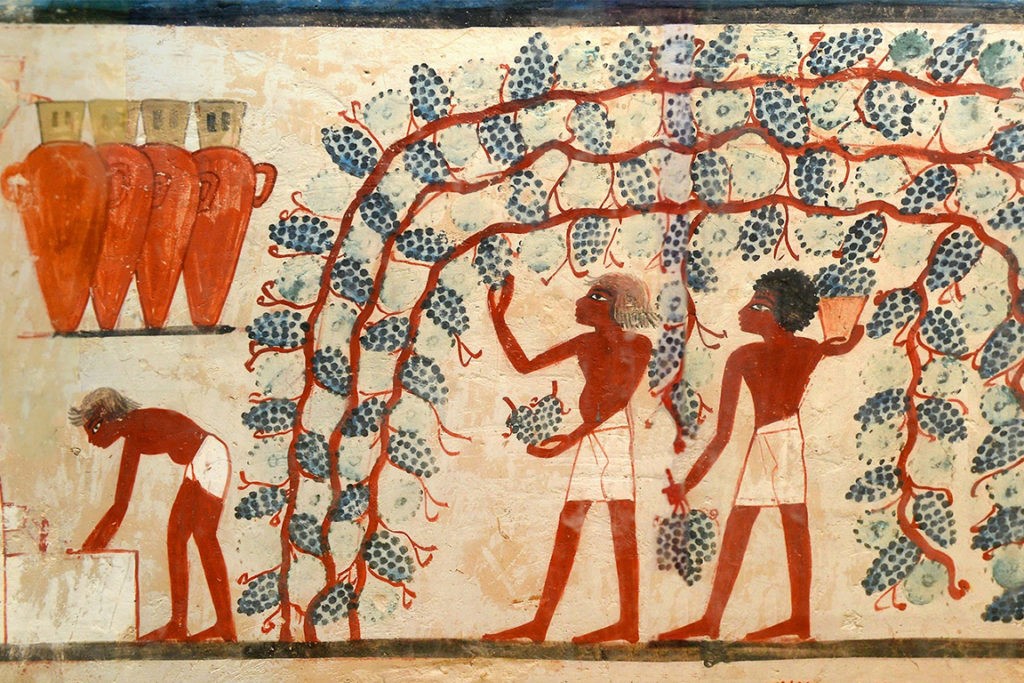

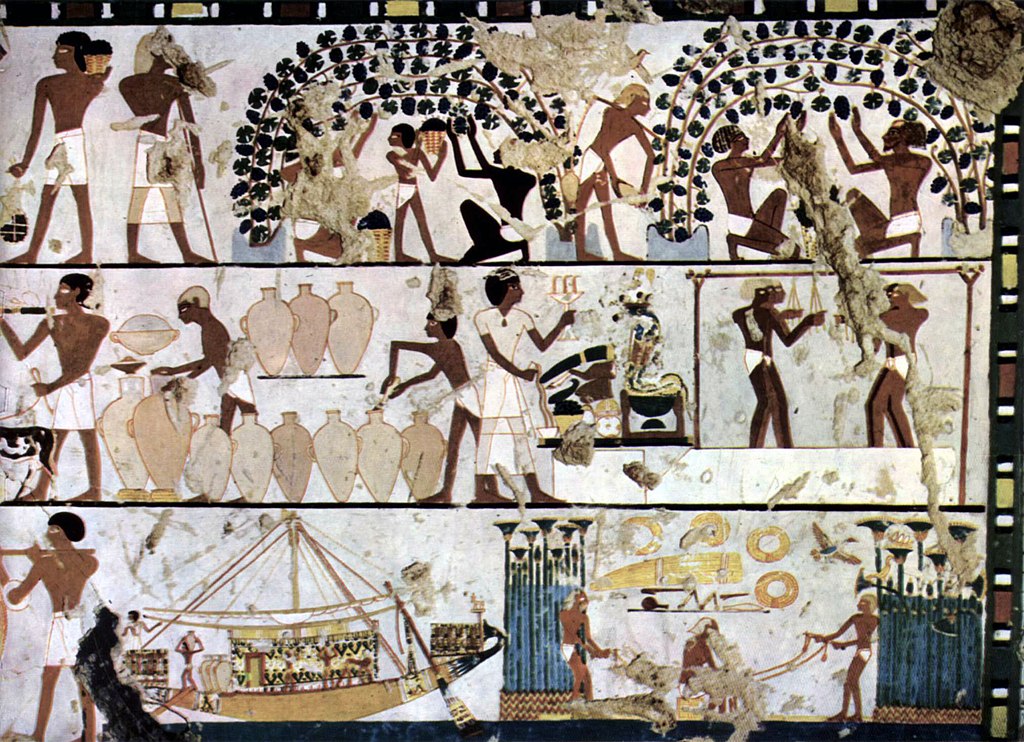

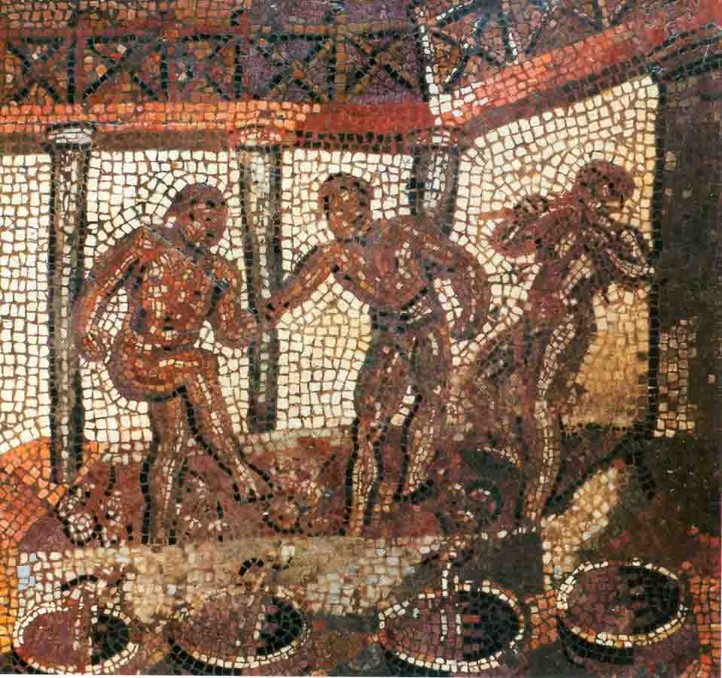

By the end of the 4th millennium BC, the wines from the coast of the land of Israel were sufficiently known to become export products, as evidenced by the amphorae found inside the tomb of Hedj Hor (3,200 BC) in Abydos, one of the oldest cities in Upper Egypt. Through the trade relations that occurred during Antiquity, the consumption of wine, and subsequently the cultivation of the vine, spread throughout the Mediterranean Sea area. The first representation of the winemaking process was made by the Egyptians during the 3rd millennium BC on bas-reliefs depicting scenes of grape treading (around 2500 BC).

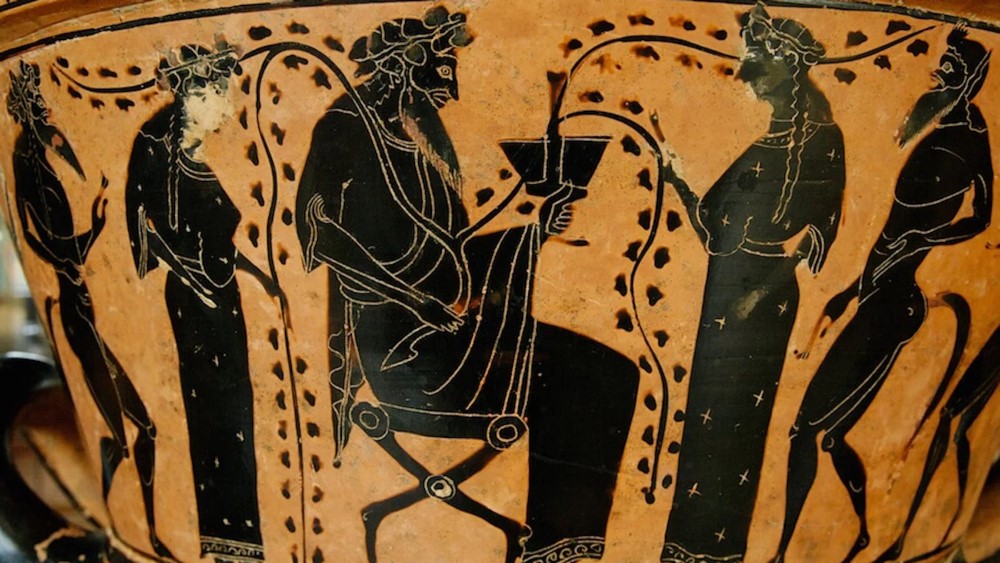

In the ancient Near Eastern civilizations, the main beverage was beer, which was consumed daily due to its ease of production. The development of wine, on the other hand, required greater control, and its preparation technique spread more slowly, starting from the archaic world of Ancient Greece. Vitis vinifera was introduced to Babylon at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, simultaneously with the apple and the date palm. The grapes thus produced were consumed fresh or dried or were destined for their processing into ‘raisiné,’ a syrup obtained from boiling unfermented must, still produced in Turkey under the name ‘Pekmez.’ The archives of Mesopotamia testify that in the ‘land between the two rivers,’ wine was always perceived as coming from an unspecified ‘elsewhere,’ from the mountainous areas towards the land of Armenia or the Syrian region. In Babylon, it was called ‘mountain beer’ (šika šadî); the oldest Mesopotamian text relating to wine is an inscription by the ruler of Lagash Urukagina dated to 2340 BC, in which it is stated that ‘a storage house for mountain beer kept in jars’ had been built. Among the Hittites, the vine, a symbol of vitality and fertility, was associated with the foundation rituals of new buildings, the purification of cities or dwellings after a funeral, and libations. In Hittite civilization, wine was generally consumed mixed with water, sometimes with the addition of honey and/or olive oil. Legislation punished damage caused to vineyards, providing for the arrest of offenders and compensation in case of fire. It would seem that local production was entirely insufficient for their needs, and therefore the kingdom seems to have often resorted to supplies from other areas (Cilicia, from Karkemish, and from Ugarit). Present-day Lebanon is also among the oldest sites in the world for wine production. The Phoenicians of the coastal strip were primary instruments in the spread of wine and viticulture throughout the Mediterranean. The use of amphorae for transport was widely adopted, and the grape varieties from Phoenician territories were important in the development of the wine industries of both Ancient Greece before and Ancient Rome later. The only recipe of Carthage that survived the Punic Wars was that of Mago the Carthaginian for making passum wine, a variety that later became popular in the Roman Empire as well. Much of modern wine culture derives directly from the practices implemented in Ancient Greece. Many of the grapes cultivated in modern Greece are unique and very similar or identical to the varieties grown in ancient times; in fact, the most popular of contemporary Greek wines, a strongly flavored white wine called Retsina, is believed to be a ‘carry-over’ originating from the ancient practice of coating wine-containing pitchers with tree resin, which imparts a distinctive flavor to the beverage. The Greeks knew of three types of wine: white, rosé, and red. Ubiquitous in Greek literature, wine inspired the mythology concerning the god Dionysus with his entourage of Maenads, Satyrs, and dancing Centaurs, and where – among others – the figures of Priapus, Pan, and Silenus stand out.

The great Greek wines were considered precious goods throughout the Mediterranean Basin; one of the most famous is the ‘Chian’ from the island of Chios, which is credited with being the first branded Greek red wine, although in truth it was known as ‘black wine.’ The cultivation of the vine was introduced to Gaul by Greek colonists, while wine was brought by Etruscan merchants at the end of the 7th century BC. The development of Gallic wine took place between the 6th and 5th centuries BC, only to disappear and then subsequently reappear during the 1st century BC; in fact, only Roman citizens had the right to plant vines in Gaul. The mass import of Roman wine therefore continued until the 1st century BC. After the conquest of Gaul, members of the local aristocracy could no longer use the trade in Roman wines to guarantee their political domination; Gallic viticulture therefore spread rapidly throughout the Mediterranean basin. Consumption was reserved for banquets, more as a marker of prestige, far from the popular opinion of it being a common commodity. It is in this period that the French wine tradition was born.

The most important wine-producing estate of Antiquity, the ‘Villa di Molard,’ was discovered south of Donzère (Rhône-Alpes region) and extended over 2 hectares. The estate, dated between 50 and 80 AD, must have produced at least 2,500 hectoliters annually. The yield of Roman vineyards has been estimated at 12 hectoliters per hectare. All or part of its production was shipped in barrels along the Rhône. The production of Gallia Narbonensis began to compete with Italian wines. The vineyards of Bordeaux, Languedoc, and along the Rhône flourished; the vine thus reached Île-de-France, which would remain for a long period one of the major French wine regions. The Gallo-Romans expanded wine cultivation, improving winemaking processes with the technique of aging in oak barrels. The irreversible decline of the Roman Empire during the 5th century AD would significantly influence the development of Gallic agriculture.

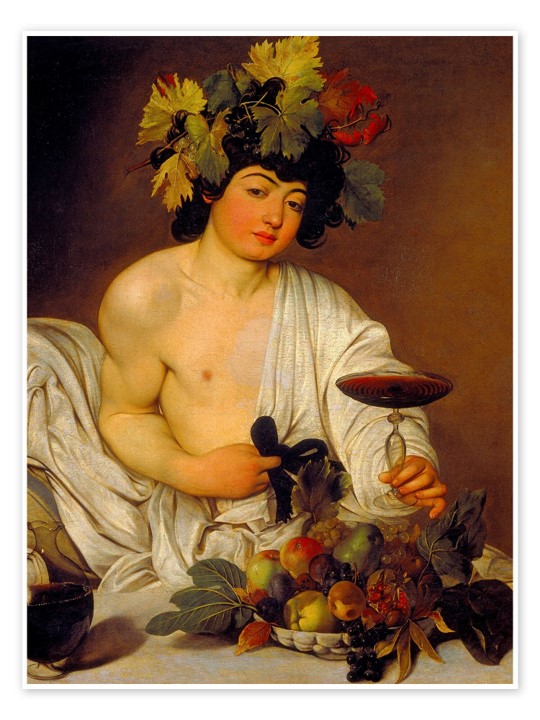

The Romans developed viticulture and its industry by assimilating knowledge from the Phoenicians and the Greeks. The Roman Empire had an immense impact on the development of vine cultivation and oenology; wine was an integral part of the Roman diet, and winemaking became a precise commercial activity. Virtually all the wine-producing regions in Western Europe were established during the early imperial era. The extent of the Empire also led to the expansion of the ‘cult of wine’ following in the footsteps of the Roman legions. The Dionysus of Greek mythology transformed into the Latin Bacchus, to whom a special cult was dedicated, as demonstrated by the Villa of the Mysteries in ancient Pompei.

At the beginning of the Christian era, the grapevine progressively spread to the Hispanic and Gallic regions, eventually reaching Britannia. Viticulture expanded to such an extent that the Roman Emperor Domitian was compelled to promulgate in 92 AD the first laws expressly aimed at wine, prohibiting the planting of new vineyards in the Italian peninsula and ordering the uprooting of a good half of those present in the provinces; this was to increase the production of grain, which was more necessary but less profitable. Winemaking technology improved significantly during this period, during which vinification, obtained mainly from black grapes, was without maceration, and therefore the wines were – as in antiquity – light in color. The juice was generally collected after a simple crushing, and pressing was immediate. Wine presses had been known for a long time but were heavy and very expensive machines, so very few wineries could afford them. Many different varieties of grapes and cultivation techniques were created. Wooden barrels invented by the Gauls and glass bottles (the work of the Syrians) began to compete with terracotta amphorae for storage and shipping. The Romans also invented a precursor to modern appellation systems, as some regions managed to earn a certain reputation for the production of fine wine; the most famous was the white Falernian from the border area between Latium and ancient Campania. When the Western Roman Empire fell in the 5th century AD, the entire European territory entered a period of social turmoil following the barbarian invasions, with the Roman Catholic Church as the only stable civil structure; it was precisely through the Church that winemaking technology and viticulture in general, essential for the celebration of Mass, managed to preserve themselves intact. From the 4th century onwards, Christianity contributed decisively to the strengthening of the value attributed to wine; the liturgy of the Eucharist under both species (bread and wine), practiced until the 13th century, was one of the driving forces behind the maintenance of the viticultural tradition. The medieval era also saw progress in the quality of wine; while ancient wines were almost always cut with water and made more palatable with the use of herbs and aromas, wine in the form we consume it even today appears precisely in the Middle Ages. The expansion of Christian civilization was also at the origin of the expansion of viticulture in the world. The true custodians of quality turned out to be the monks, who perpetuated the tradition of wine; cathedrals and churches owned vineyards, converting the activity to the production of ‘Mass wine.’ Monks managed monastic vineyards, helping in the creation of the qualities that exist today.

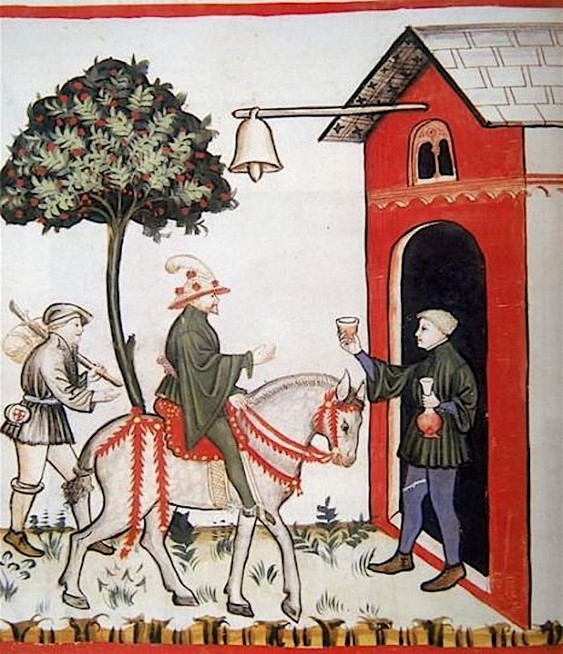

In its generality, wine assumed the role of a commercial industry precisely during the Middle Ages with continuous trade in the Near and Middle East, as a raw material for the distillation processes of Muslim scholars of Alchemy aimed at achieving the Magnum Opus; they managed to produce relatively pure ethanol, mostly for use in the perfume industry. It was during this period that wine was distilled into brandy for the first time. Throughout the medieval era, wine was the common beverage of all social classes in Southern Europe, a region where grapes were diligently cultivated. In Northern and Eastern Europe, where few cultivated grapes, beer and Ale (the term used to indicate top-fermented beers) were the usual drinks of both the common people and the nobility. In the Nordic regions, wine was imported, but due to the relatively high cost, it was rarely consumed by the lower classes. However, since wine remained a necessity for celebrating Catholic Mass, ensuring its regular supply became crucial. In medieval France and the Holy Roman Empire, monks of the Order of Saint Benedict (6th century) soon became among the largest wine producers, followed by the Cistercian Order. Medieval monks made winemaking their primary mercantile sector, producing so much wine that they shipped it to every corner of Europe for ‘secular’ uses. In the Kingdom of Portugal, one of the countries with the oldest wine tradition, the world’s first appellation system was created. Medieval France remained the main exporter of wine; Paris and Île-de-France hosted the largest vineyards of the kingdom, supplying the cities, which were the main consumers. Red wine developed in French territory subsequently spread throughout Western Europe starting in the 14th century; in fact, until that time, the most appreciated wines had been white and rosé.

In 1435, the Lord of the County of Katzenelnbogen, John IV, a wealthy member of the nobility of the ‘Holy Roman Empire’ near Frankfurt, was the first to plant and cultivate the Riesling variety, which soon became the most important German grape. Wine was traded in barrels between the different provinces or states and was sold retail in taverns where the price was loudly announced at the entrance by an employee who invited passersby to taste the new wine.

Until the 17th century, wine remained the only beverage produced on a massive scale according to a consolidated tradition. Only with the increase in the share of Northern European beer and colonial imports of tea, coffee, and chocolate did new habits begin to take hold. The European colonization of the Americas by the Spanish and Portuguese caused a rapid expansion of vineyards, almost doubling their yield. The step from Latin America to North America was short, but it was mainly due to the waves of immigration of Italians, French, and Germans, who brought their own wines with them, that local production began.

In an oenological context, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa are considered the new world producers. Viticulture began in the then Cape Province as early as the 1680s as a substitute activity for supplying transit ships. Until the end of the 20th century, the product of these countries was not well known outside small export markets. Australia mainly exported to the United Kingdom; New Zealand kept most of its wine for domestic consumption; South Africa was often isolated from the world market due to apartheid. However, with the increase in agricultural mechanization and scientific advances in winemaking, these countries began to gain attention for their high-quality wine. It must also be said that the highest quality wine producers in these countries are of Italian origin, particularly from Friuli and Veneto.

Leave a Reply