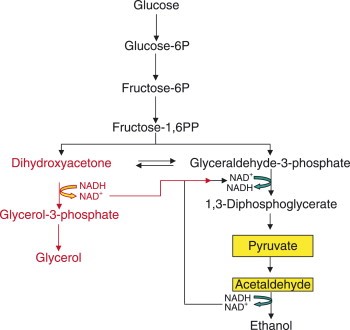

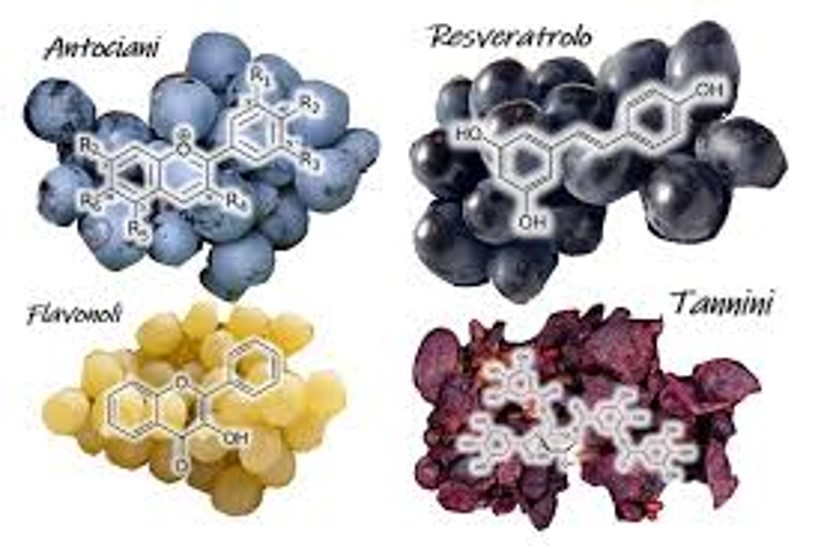

In this article, we delve into a very sensitive topic: is drinking wine good or bad for you? On one hand, there’s history, tradition, and also the pleasure of drinking a nice glass of wine, with the positive support of some nutritionists. On the other hand, we find an increasingly large group within the medical-scientific community asserting the toxicity to health of this beverage, just like any alcoholic product in general. It should be noted that the interests of many countries are significant, as wine production is an important item in the economy of the producing country, with a considerable weight on its trade balance. Added to this is that the European Parliament, likely influenced by the alcohol producers’ lobby, has recently reintroduced the idea that moderate alcohol consumption may not be harmful, obviously amidst criticism from both the oncology and the majority of the cardiology community, with recent studies that have instead confirmed that there are no safe dosages, not even for the heart. But before we continue, let’s see what wine contains… specifically red wine, which is indicated by some as a ‘drink’ that ‘makes good blood’ if consumed in moderate quantities. Red wine is a beverage obtained through the alcoholic fermentation of grape must. In practice, the production process involves the transformation of sugars contained in the grapes into alcohol and carbon dioxide, thanks to the presence of yeasts. Consequently, the main substances contained in wine, besides water, are ethyl alcohol (or ethanol) and sugars. Depending on the type of treatment and the production method, the percentage of these ingredients can vary. There is also, in smaller quantities, a whole series of substances that contribute to the flavor, smell, and color. We are talking about organic molecules naturally present in grapes or formed during the fermentation process. In particular, polyphenols are primarily responsible for the color, flavor, and sensation of astringency in red wine.

The belief that drinking a few glasses of wine or beer is a behavior generally perceived as ‘not potentially dangerous’ from a health perspective is quite widespread, despite the fact that the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified alcohol as a carcinogen as early as 1988, with an increasing number of studies showing a clear association between alcohol and numerous forms of cancer. Yet, according to the results of some scientific research, some might even think they could derive a health benefit, particularly for the heart, from moderate alcohol consumption (Some epidemiological studies seem to show that moderate wine consumption is associated with a decrease in mortality from cardiovascular diseases. This benefit is attributed to its antioxidant properties, the positive effect on lipids, and the anti-inflammatory effect). However, the results of a British study published in the journal Clinical Nutrition highlight how this conclusion is incorrect due to significant inaccuracies in the method of analysis. Numerous scientific studies have evaluated the effect of alcohol on the heart and blood vessels. In some, researchers analyzed the risk of stroke, heart attack, or death in relation to the number of alcoholic beverages consumed each day, finding a trend resembling a ‘J’, meaning it would seem that those who do not drink would have a higher level of cardiac risk than those who consume modest amounts of alcohol. However, this conclusion has never truly convinced experts. Researchers from Anglia Ruskin University and University College London went on to examine the database of the UK Biobank Study in this regard. This is a collection of epidemiological data, started in 2006-2010, in which half a million British citizens participate on a voluntary 1 basis. In the part of the analysis focused on alcohol and cardiovascular risk, the researchers examined about 350,000 participants. Of these, 333,000 had reported consuming alcohol, in various quantities and frequencies, while almost 22,000 had instead said they had never consumed alcoholic beverages, not even occasionally. Participants had been asked how much alcohol they consumed weekly, and what type. Based on the answers, people who reported consuming less than 14 units of alcohol per week were placed in the moderate consumption category, while those who consumed more than 14 units were placed in the high consumption category. One alcohol unit (AU) corresponds to 12 grams of ethanol; a can of beer (330 ml), a glass of wine (125 ml), and a shot of liquor (40 ml) each contain approximately one alcohol unit. Guidelines recommend not exceeding two alcohol units per day for men and one alcohol unit per day for women. Once the participants were divided, the researchers looked at how many hospitalizations due to cardiovascular events had occurred in the two groups during the approximately seven-year observation period. Compared to drinkers, we confirm that those who have never consumed alcoholic beverages seem to have a higher cardiovascular risk,’ the research authors write. However, the non-drinkers included in the study were found to be less physically active, with higher body mass index and blood pressure. It is therefore likely that many of them did not consume alcoholic beverages because they were not in good health. To support this interpretation, the authors of the article cite a study that observed that people who already suffered from a chronic disease from the age of 20-30 were highly likely not to consume alcohol even in later years. Therefore, comparing the cardiovascular risk of drinkers with that of non-drinkers would introduce a systematic error (what is called ‘bias’ or distortion in statistical analysis) that leads to an underestimation of the effect of alcohol or even to seeing a protective effect on health. A second distortion would have been introduced by considering the consumption of alcohol units in general, without distinguishing where they came from. Those who drank beer and spirits, even in moderate quantities, had a higher risk of ending up in the hospital for an event involving the heart and blood vessels. This risk appeared lower for those who drank wine, but only if all types of events were considered together. If, instead, ischemic heart disease was excluded, the protective effect disappeared. Ischemic heart disease is a condition in which the heart muscle does not receive enough blood and oxygen, often due to problems with atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries. Indeed, there is data suggesting that some molecules contained in wine are beneficial for the coronary arteries, an element that is not sufficient to start drinking anyway. ‘Even if wine drinkers may have a lower probability of developing coronary artery disease, our data reveals that the risk for these people of experiencing other cardiovascular events is not reduced,’ the research authors emphasize. The authors’ conclusion is: ‘We have shown that, if we consider these two distortions in the analysis of general cardiovascular risk, alcohol has no protective effect on health and, in fact, is associated with an increased cardiovascular risk even when consuming 14 or fewer alcohol units per week.

So, there is no safe amount of alcohol: the beneficial effects of polyphenols in red wine must be weighed against the negative effects resulting from ethanol.

Regarding the ‘beneficial’ effects of polyphenols contained in red wine, a study published in 2016 in the American Society for Nutrition stated that to achieve the beneficial effects of resveratrol (one of the polyphenols present in wine), we would need to drink about 2000 liters of red wine per day, or about 16,000 glasses a day to get the cardioprotective effect. This is because the amount of resveratrol in wine is around a few milligrams per liter and is often even degraded by our body. A similar argument applies to anthocyanins, another category of polyphenols, which give wine its characteristic red color and are also antioxidants, but to get the beneficial daily dose, we would need to drink 5 liters of wine per day (minimum daily amount 550 mg, while 1 liter of wine contains 130 mg), whereas with 100 grams of blueberries, we would reach the desired amount without the negative effect of ethanol.

Therefore, it is evident that the much-touted cardioprotective effect of polyphenols is practically ZERO! Indeed, the ethanol contained within it is a substance that has much more potent and harmful negative side effects than any possible beneficial effect of wine. Therefore, there is no safe amount of alcohol: according to the WHO, ‘it is not possible to identify recommended or “safe” levels of alcohol consumption for health.

In any case, an amount of ethyl alcohol below 10 grams per day (a maximum of about 100 ml of wine, a can of beer, or a shot of liqueur) is considered ‘low risk’, but unfortunately, a zero-risk amount does not exist. Furthermore, as better specified in another article that you will find at the following link:

https://www.meteogourmet.it/bevande-alcoliche-alcune-curiosita-ed-effetti-sullorganismo-umano/

From a nutritional point of view, wine, like any other alcoholic beverage, is not considered a food because it does not contain nutrients. On the contrary, prolonged intake of alcoholic beverages could cause dysfunctions in the absorption of other active ingredients. Beyond that, alcohol affects mental health, very often negatively, as it influences brain chemical processes. While occasional minimal consumption might make you feel happy, calm, talkative, and seemingly more confident, consistent consumption, even moderate, could increase the risk of depression, panic disorders, and impulsive behaviors with a loss of self-control. You can find more detailed information about the damage caused by alcohol to the brain at the following link

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7177420/

What is my position on this topic? Like many ‘boomer’ guys, when I was young, drinking beer was fashionable, but I was an occasional consumer, less occasional in the summer (a nice cold beer initially gives pleasant sensations, but then…), just as I would have a few glasses of grappa or other spirits in the winter, especially in the mountains… but then, how many haven’t ever had a small glass of nocino, limoncello, licorice liqueur, or myrtle liqueur? Then, with age, I moved on to preferring wine, so much so that I took a basic sommelier course, fascinated by the culture and history behind this drink. And I was convinced too by the false positivity of a glass of red wine a day. Only recently have I delved deeper into the subject (thanks also to my daughter’s studies) and I have completely stopped drinking. Although I wasn’t a serial drinker, in fact, I couldn’t even be considered a drinker, when I do try, once in a while, on special occasions, to drink a glass of prosecco or wine in general… well, I feel it, it bothers me a bit, as if I’m circulating something harmful for my body after detoxifying it. However, the property that a glass of wine has to make convivial activities pleasant, combined with that slight release of inhibitions it produces with a ‘low risk’ of potential harmful effects, once in a while it can be done, even accepting the damage to some neurons… but I repeat, sometimes it’s worth it! Cheers!

Leave a Reply